The busy university town of Urbino is often called ‘the perfect Renaissance city’ – and indeed the birthplace of Raphael rivalled Florence and Siena in its day. Joe Gartman returns to find out if they have got any of their loaned out paintings back yet…

Standing at the Punto Panoramico, near the walls of the forbidding Albornoz fortress overlooking Urbino, it is difficult to avoid a certain gentle melancholy. It’s Sunday, the last morning of our weekend in the city of Federico da Montefeltro. Below us, houses of rose-tinged brick line the narrow streets, and the city seems to embrace the beautiful palace. It’s a scene that speaks of past glories, like a story from an old volume in the Duke’s famous library. Urbino’s past might seem to be a romance, or a legend like Arthur’s fabled Camelot; for, once upon a time long ago, in Urbino as in Camelot, the ideals of gentility, honour, and nobility flourished. But in Urbino, it wasn’t an imagined, poetic idyll. The story was true.

Urbino’s hills rise from the Adriatic coast and the city is perched in serene isolation among them. The nearest rail station is in Pesaro, a coastal town 20 miles away. Urbino is often called the “perfect Renaissance city”, but it’s not an empty set within its stone walls. It’s a lively town that hosts a busy university. It has several serious claims to fame, beginning with Duke Federico himself, the great general-for-hire who ruled wisely and peaceably over his own small domain. There’s Raphael, too, the local kid who made good, and Giovanni Santi, court painter and Raphael’s dad. Piero della Francesca worked for Federico at one time, and so did Pedro Berruguete, a Spanish painter of genius who made a brilliant portrait of the Duke and his son, Guidobaldo. The National Gallery of the Marches, housed in the Ducal Palace, contains paintings by these worthies as well as by Titian, Paolo Uccello, and Melozzo da Forli.

Federico’s Ducal Palace is a work of art in itself. It is widely held to be the best and most beautiful of Italian Renaissance palaces, and I certainly can’t argue the point. The cortile is an elegant demonstration of ideal Renaissance proportions. Graceful arcades surround the courtyard, and there is an undeniably comfortable feeling of harmonious, human scale. It was designed by Luciano Laurana, from Dalmatia, across the Adriatic. Luciano was responsible for much of the palace, but left town mysteriously after 12 years and was replaced by other architects, whose identities are hotly argued among scholars. Donato Bramante may have been one.

The palace, and its art collection, deserves at least a whole afternoon’s attention. So, on Friday, after checking into our B&B at the top of steep Via Raffaello, we tripped lightly down the hill toward Piazza della Repubblica, blithely ignoring the fact that we would have to trudge back up in the evening. The entrance to the palace is opposite the Duomo, just a couple of blocks past the piazza.

The rooms in the palace are mostly bare of decoration, but their vaulting is elegant and their fireplaces very grand. It is a perfect setting for the world-class collection of art. My favourite piece may be the mysterious Flagellation by Piero della Francesca. It’s startling because far in the background, Christ is being flogged; but dominating the picture in the foreground are three exotically dressed men ignoring the scene and having a casual conversation. I sure wish I could talk to Piero or the Duke and find out who they are!

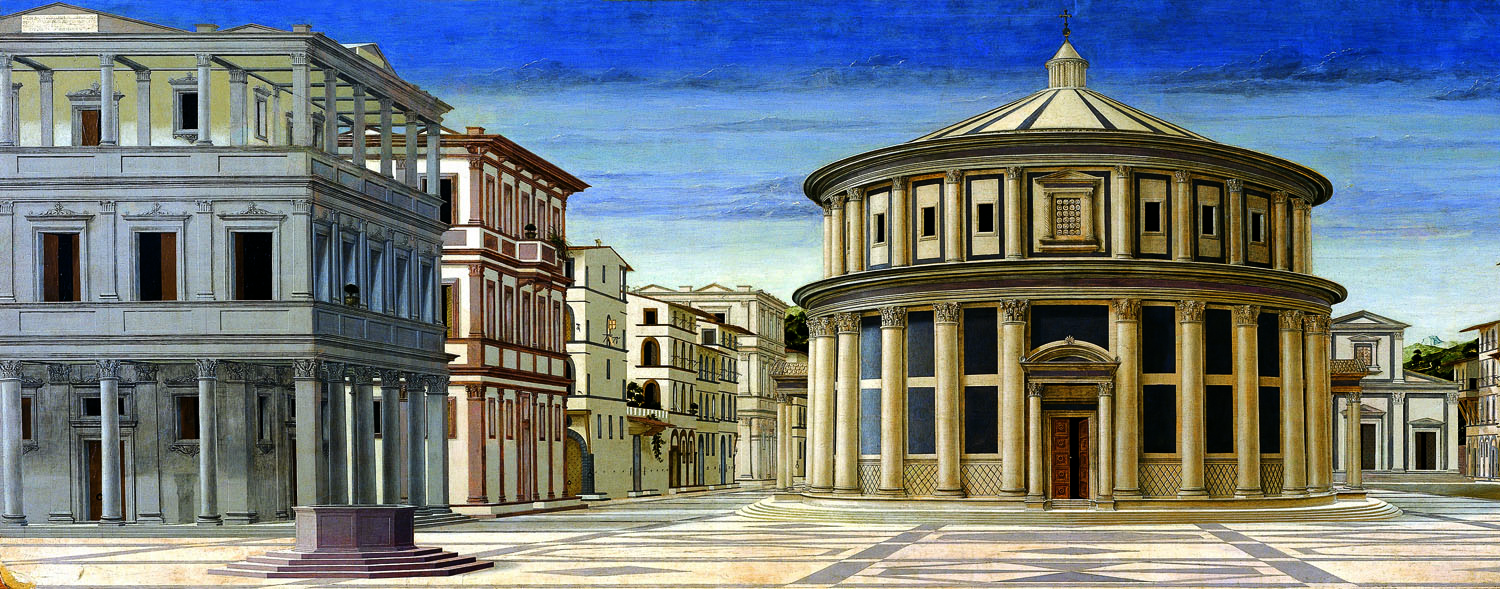

Another striking painting, possibly by Piero, is an exquisitely detailed view of an impossibly perfect Renaissance city – perfect perspective, perfectly proportioned buildings, a piazza in the foreground perfectly spotless, no litter, no animals, no pigeons, no dirt – and no people. It’s called La Città Ideale – The Ideal City. If there was ever a painting of silence, this is it. There is no consensus about who painted it. I asked the guard if he thought it was Piero’s work. “It’s a painting of architecture, no?” he said. “Beautiful, like the palace. Piero was a genius, a great painter, but Laurana was a painter, too, and architect. Laurana painted it – sicuramente!” I’m inclined to agree with him; he seemed a man of discrimination – after all, he complimented my Italian! (At least I think he did.)

I wanted to see Piero’s Madonna di Senigallia, but it had been loaned for exhibition elsewhere – again. This Madonna is a peripatetic lady; she was on loan the last time I was here, too, and that’s not the first time she’s been missing. In the 1970s she was stolen as part of a large art heist, but luckily was recovered in Switzerland.

Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Woman – La Muta, had also been loaned last time, and this time she was away for restoration. I wish I could have seen her in person. In the photos I’ve seen, she seems to have her mouth set rather firmly, as if she had nothing more to say and dared anybody to ask. La Muta, indeed. Ah well – I hope to return to Urbino again, and third time’s the charm!

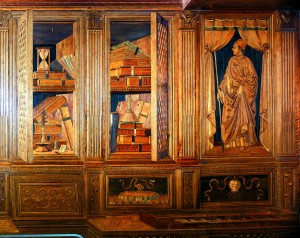

Wandering around the palace, (and sometimes you can wander around quite a lot without meeting anyone), you’ll eventually come to a cozy room lined with wooden cupboard doors. You’ll be surprised, at first, that some of the doors are ajar, exposing the cupboard contents: jumbled books, candlesticks, hourglasses, musical instruments and much more. But all the objects have the rich, golden hue of fine varnished wood, and you soon realize the cupboard doors, miracles of illusionistic intarsia woodwork, are closed. The skilled artisans who created them are not known by name. Some scholars have suggested that Botticelli may have had a hand in the design. Above the cabinets are portraits of great men, including Dante, Homer, Solomon and Petrarch. This room was Duke Federico’s studiolo, and it is the most famous of such places in Italy. Just a few steps away from the studiolo is the balcony from which the Duke could survey his domain.

Down a small set of stairs, the Duke could visit his two small private chapels, one Christian (the Cappella del Perdono) and one pagan (the Tempietto delle Muse). An inscription says, approximately, “These small chapels are united with only a little difference: one is sacred to the Muses, and one to God.”

The Duke’s interest in the Muses, even having a chapel dedicated to them, is an indication of his interest in classical Greek and Roman thought, an interest he shared with other humanists of the Renaissance. His court became an important center of artistic and intellectual activity, second only to Florence in fame. It is ironic that the greatest testament to the glory of Urbino’s court, Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, dealt with events after Federico’s death.

Published in 1528, the book describes conversations that took place in the palace while Federico’s son Guidobaldo was Duke. Ladies and gentlemen of the court discussed ethics, friendship, love, honour, and the duties people owe to each other. Guidobaldo was an invalid, so his Duchess, Elizabetta Gonzaga, presided over the gatherings. Castiglione’s work was hugely influential in its time, and cemented Urbino’s reputation as a centre of civilized grace and culture.

Having stood on the Duke’s balcony – well, actually, a balcony one floor below his, but who’s counting? – we began the trudge back up Via Raffaello. A number of young people were climbing the hill, too, probably students heading for the Accademia di Belle Arti. I felt a rather perverse pleasure hearing them gasping a bit, as I was, but they passed me anyway.

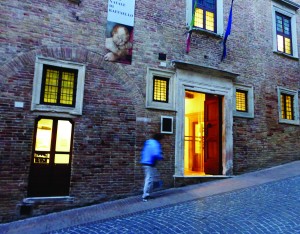

We paused for breath and noticed, at number 57, that the brick façade sported an impressive marble portal around tall, double wooden doors. We’d found the childhood home of Raffaello Sanzio, the great High Renaissance painter known to English speakers as Raphael. We decided we had just enough time to visit; besides, it gave us a perfectly good excuse for a breather.

Inside, the house is a handsome example of a 15th century urban home. Raphael’s family evidently lived comfortably – there are arched doorways, large fireplaces, and lovely, mullioned windows. Raphael’s father, Giovanni Santi, was court painter to Duke Federico, who appears to have treated him well. (Giovanni was dismissed by Vasari as a “pittore non molto eccellente” – not a very good painter. Vasari didn’t know it at the time, but this would become his own future reputation.)

Unfortunately, there are no works by Raphael in the house, barring a Madonna that may have been an early work. There are copies of some of his paintings, including the portrait of La Fornarina, Raphael’s purported mistress. A surprising object is an odd statue of Raphael, aged about 12, with long hair and wearing a dress. He looks exactly like a young girl.

At any rate, Raphael was not only a roaring success after he left Urbino, but was reputed to be a very amiable fellow whose early death grieved everyone who knew him, except, possibly, a few artistic rivals. Maybe it was his small-town background that accounted for his likeability. Or perhaps the virtues of the Montefeltro court existed even before Castiglione, and influenced the young son of the Court Painter.

On Saturday morning we found a lively market just outside our windows, with stalls beneath the trees lining Viale Buozzi. Flowers, clothes, shoes, fruit and vegetables, meat and fish, cheese – it was a colourful array that extended nearly a half-mile along a ridge, with sweeping views over the countryside. I enjoyed the stroll, but avoided the fishmongers – too many beady eyes staring reproachfully from beneath the glass.

After coffee and a cornetto semplice, we were ready to visit the Oratorio di San Giovanni, a small church built in 1365. It is nestled at the end of a small street, a humble little structure in the Gothic style. It has served as a hospice for the sick, and as the home of the Brotherhood of San Giovanni Battisti since 1395. On its walls are famous frescoes by Lorenzo and Jacopo Salimbeni, two brothers who were important late-Gothic artists. Imagine our dismay when we found the church filled with scaffolding. Dismay became delight when we were invited to climb up and get a close look at the colourful scenes of the life of St John (a rare opportunity). We watched the restorers at work; I must say it seemed almost surgical – a young man tap-tap-tapping the plaster, and then injecting material into the hollow between the wall and the fresco with a giant syringe.

In the evening we strolled in the park at the top of Via Raffaello, with a monumental statue of the artist at its centre, and busts of other famous Urbino residents. Giovanni Santi, Donato Bramante, and Piero della Francesca are all there, of course. The park has great views, and a strange characteristic: as you climb Via Raffaello toward it, the statue seems to rise up from the crest of the hill, as if Raphael is emerging from the earth.

In the evening we strolled in the park at the top of Via Raffaello, with a monumental statue of the artist at its centre, and busts of other famous Urbino residents. Giovanni Santi, Donato Bramante, and Piero della Francesca are all there, of course. The park has great views, and a strange characteristic: as you climb Via Raffaello toward it, the statue seems to rise up from the crest of the hill, as if Raphael is emerging from the earth.

We watched the sun set as Raphael quietly surveyed his hometown, where long ago people dreamed of La Città Ideale. And next morning we stood at the Punto Panoramico to say goodbye. I thought of Castiglione and his famous book, which is tinged with sadness. By 1527 Rome had been sacked and the political map of Italy changed day-to-day as easily as an etch-a-sketch.

Castiglione knew that the cultured ease of Urbino was doomed. Many of the people he wrote about were dead before the book was published. He remarked, as if saying farewell: “Nor do I believe that the sweetness that is had from a beloved company was ever savoured in any other place, as it once was there.”

The grace of the Renaissance still inhabits Urbino: the beauty and harmony of the palace, and the art within; the perfect hilltop setting of the city; the views from the Duke’s balcony over green, rolling hills; the University, still a seat of learning after 500 years. The city remains a symbol of all that was noble and harmonious long ago, when a few Italian towns awoke from their long Medieval slumber.

Click here for all the top tips on where to stay and eat, what to see and do and how to get there!