Vincenzo Scamozzi’s final touch for the Olimpico was an amazingly detailed, three-dimensional stage set behind the scaenae, depicting the ancient city of Thebes

Andrea Palladio channelled the great Roman architect and writer Vitruvius, studied Roman ruins, and added his own Renaissance ideas. With his Quattro Libri dell’Architettura (Four Books on Architecture), he dominated grand-building design in Britain and America for two centuries after his death. Great builders from Inigo Jones to Thomas Jefferson were inspired by his work.

Palladio died in 1580. All the buildings he himself designed are in the Veneto; a few are in Venice, but most are in and around Vicenza. The famous Villa Rotonda is just outside town. The last and most unique of his works, though, is on Piazza Matteotti, near the top of the central street named for him, Corso Andrea Palladio.

You enter through a tall arch cut through a medieval wall, into the courtyard of an old fortress and former prison; then, through a hallway, you emerge like a time-traveller from the Middle Ages into nothing other than… Ancient Rome. In fact, you are in Palladio’s indoor version of a Roman theatre as it might have appeared in the 1st century BC. It’s called the Teatro Olimpico.

Palladio was a founding member of the Accademia Olimpico in Vicenza, and the organization had acquired the disused prison. Palladio’s dream was to recreate a classical Roman theatre inside it, complete with an elaborate scaenae frons, for Vicenza. (The scaenae frons was a building that served as a backdrop for the performance area in Ancient Roman theatres.) Purpose-built theatres were very rare in Palladio’s day; only three survive from that era – besides the Olimpico, there is one in Parma and one in Sabbioneta, near Mantua.

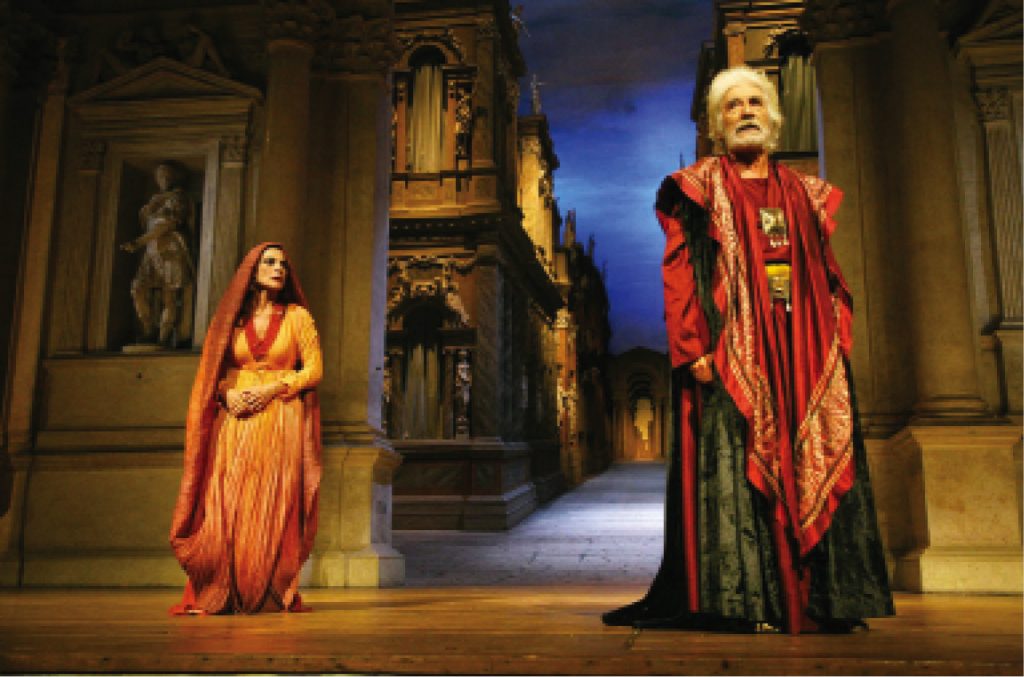

The site was difficult: the old structure couldn’t accommodate the usual Roman semi-circular seating area, so Palladio had to settle for a half-ellipse. The scaenae frons, though, is pure Palladio: there are columns, a grand central arch, doorways, and statues of Accademia members in the niches. It is handsome and elegantly proportioned: Palladio at his finest.

But it is upstaged – very literally – by what is glimpsed behind it, through the grand arch and doorways. Palladio died before the theatre was complete, and his successor, Vincenzo Scamozzi, finished it. Scamozzi’s final touch for the Olimpico was an amazingly detailed, three-dimensional stage set behind the scaenae, depicting the ancient city of Thebes – chosen because the first production presented there was Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex. The scene is utterly convincing, with streets seeming to extend into the distance, and real buildings lit from within.

It is a triumph of false perspective, created in just a few metres of space. If an inattentive actor happened to stray beyond the arch, in three steps he would loom as large as Godzilla, and probably destroy Thebes for ever. The set is still there, however; it’s the oldest existing stage set in the world. The theatre, too, is more than 400 years old. You can still attend plays there. If you do, though, try to forget what I’ve just told you. Otherwise, if you look behind the scaenae, they’ll all take place in Thebes.