Lisa Gerard-Sharp discovers that skippering your own boat is the best way to see Venice at a leisurely pace – and it’s easier than you’d think…

Henry James thought that, “Everyone interesting, appealing, melancholy, memorable or odd” gravitated towards Venice. That’s our lame excuse – we must be “the odd”. We are an accidental all-female crew: no-nonsense Alice; dreamy Kasha and landlubber me. We make a shambolic team. Alice brings common-sense to Kasha’s sense of wonder and my bookish sense of Venice. Our roles are cast early on in our boating journey: Alice keeps us afloat; Kasha keeps us in wine and girlish good spirits; and I keep us vaguely on course, despite a penchant for Prosecco and drooling over mildewed palaces while navigating.

This is billed as a voyage for Venice addicts who are tired of battling over the bridges to St Mark’s Square. Instead, we will drift by deserted islands, once lunatic asylums, leper colonies, hermitages or monasteries. We may encounter shrimp fishermen, Benedictine monks or migratory birds. If the mood takes us, we can jump out at the port of Chioggia to buy the freshest fish, or have a picnic lunch of artichokes and fruit in Venice’s market garden. The clincher is that this is for ‘boating virgins’ rather than ‘snotty yachties’.

Although also sailing novices, the boys’ group in the other boat snub our services and sail into the sunset alone, having mastered the controls in the Chioggia lagoon before breakfast.

Sailing your own boat really helps you to feel the fragility of Venice

We go round in circles in water; they go round in circles on land. Mercifully, we have that innate female gift for begging for help when stranded on a sandbank, and they have that innate male gift for opening wine bottles and unblocking our lavatories. Mastering the en suite nautical flushing system involves pumping for Venice or being unexpectedly drenched (before cancelling your booking, bear in mind that we are incompetents).

We had picked up our boats from the marina at Chioggia, a fishing port known for its intrepid sailors. Quaking in our deck shoes, we clambered onto our boats: an old-fashioned narrowboat for the boys and a sleek cabin cruiser for the girls. We were initially seduced by our superior decks and cabins, but as the cruise went on came to appreciate the greater charm of the narrowboat – not just because we could leave the navigation to the boys and retreat to the deck for posing and Prosecco.

A vulnerable city

Sailing your own boat really helps you to feel the fragility of Venice, seen propped up by mildewed sea walls. The lagoon city has always faced the contradictory dangers of death by drowning and death by suffocation: the encroaching sea had to be tamed and the silting sands held at bay. To stop the silt from clogging the lagoon, the Venetians buttressed the mud banks, first with wooden palisades and later with stone walls. Sea water enters the lagoon through three main entrances, breaks in the sand bars (lidi) beyond Chioggia, Malamocco and the Lido.

These have served to strengthen the city’s defences and channel the cleansing tides. The breakwaters were later buttressed by the Murazzi sea walls, built of Istrian stone, and one of the Republic’s greatest feats of civil engineering. As we drift past the lagoon entrances, we see signs of Moses, the great mobile barrier that is supposed to save the city. Opinion is divided as to the flood barrier’s viability, and works are currently stalled. Still, if Venice is not to be doomed to a watery grave, the lagoon world must be protected.

The lagoon reveals itself as a floating world buffeted between the smoking oil refineries on the mainland and the fish slithering in the reeds under the water. The desolation of the lagoon waters is relieved by sightings of wild ducks, mute swans and the fragile-looking black-winged stilt. Despite their proximity, the lagoon islands are startlingly different, embracing marshland, orchards, vineyards and even beaches. These low-lying islands have barely moved on from being monasteries, munitions dumps or mental asylums and we navigate our boat between the crumbling fortifications, market gardens, and former leper colonies.

The lagoon is often dismissed as a desolate marsh but it is also a patchwork of sandbanks, salt pans and mud flats, with sections cultivated as fish farms, market gardens and vineyards. Away from the Marghera mainland, the sludge and faint stench give way to dreamy, winding creeks, with reed-cutters at work. At low tide, the mud flats off Burano are dotted with fishermen seemingly walking on water. In Palude dei Setti Morti, off Pellestrina, the fishermen have built nest-like casoni – huts on stilts. Lagoon life survives, from kingfishers, cormorants and coots to grey herons and little egrets, presumably scouting for slippery eels. Our first night’s mooring is at Vignole, Venice’s back garden, once covered in vineyards belonging to the Doge.

New pace of life

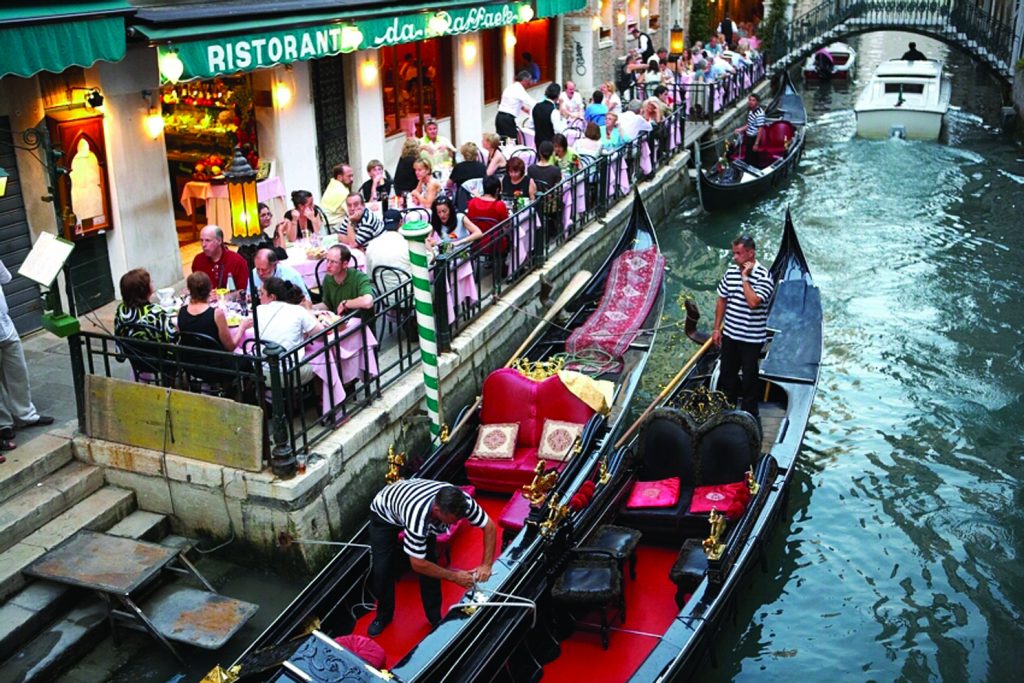

Slowly, we are settling into Venetian time and the languid pace of life on the water. In central Venice, the Venetians are well-served by vaporetti, (water buses), but on these quieter canals we are entranced by dredgers, refuse barges, and removals boats. Only the emergency services and licensed-to-kill Daniel Craig are allowed to break the gentle speed limit, rocking passing gondolas in their choppy wake. Few respect the set limit, which compounds the controversy over the dangerous wash from motorboats. The gondoliers demonstrate vociferously, but in vain.

At lunch in L’Aciugeta, we share sweet-and-sour Venetian tapas with Alessandro, a traditionalist boatman, who is pleased that the Gondoliers Association has banned “tasteless and tacky trappings” on gondolas, from garish cushions to statuettes on the prow. Custom decrees black seats and purple or midnight-blue interiors). Female gondoliers are given short shrift, so we return to our boat plotting to retrain as feminist gondoliers in another incarnation.

Taking to the islands

Sections of the lagoon are unnavigable because of the mud flats and sandbanks – only skilled boatmen can weave through these shifting channels. We know our limits and retreat to visit a cluster of contrasting islands, including San Giorgio opposite St Mark’s for its setting, Torcello for astonishing mosaics, Murano for glass and Burano for its painted prettiness. Compared with many outlying communities, these islands thrive, whether the preserve of fishermen, lace-makers, glass-makers or Benedictine monks.

Venice is a state of mind, a canvas for projecting one’s poetic fantasties

Torcello, the strangest of the islands, offers a stirring impression of the earliest Venetian settlement. The mood is set by the surreal isolation of the site, the air of stagnation, the sluggish canal, the scattered buildings, the solitary red-brick bell tower. Even today, melancholy and nostalgia await around most dark canal corners, if a ghost town is what one is seeking. Venice is a state of mind, a canvas for projecting one’s poetic fantasies.

In Murano, we are tempted by gaudy Venetian glass and soft-shelled crabs. “The most curmudgeonly of the Venetian communities, where it always feels like early closing day,” denounced writer Jan Morris. Yet Murano is proud of its past as a celebrated glass-making centre and a summer resort for the nobility. However, the rapaciousness of the remaining glass factories has somewhat blunted its appeal. On a sunny day, Murano can pass for a smaller version of Venice but lacks the stark, spiritual pull of Torcello.

Burano is a splash of colour in a bleak lagoon, with its parade of colourful fishermen’s cottages. We moor here overnight and find we have both the moorings and the rustic fish restaurants to ourselves. Ernest Hemingway was scathing about Burano: “A very over-populated little island where the women make wonderful lace and the men make bambinis.” Hemingway and Venice seem an odd pairing, though while here, he wrote a lightweight novel (Across the River and into the Trees), fuelled by heavyweight alcohol intake. We resolve to meet for cocktails in the renowned Harry’s Bar, Hemingway’s haunt, and the site of his downfall, on Venice’s mainland.

We moor in the chic marina beside the bell tower and marvel at our luck. The marina is open to all-comers but is always full by lunchtime but we manage to win ourselves a coveted spot overlooking the procession on St Mark’s Square. However, our triumph is short-lived as we fluff our mooring in a cascade of ropes, climaxing in Kasha being lassoed to the mooring post like a beached mermaid. There’s solace in the discovery that a Russian billionaire’s yacht has been turned away for being too bulky, too Russian for Venetian tastes.

After peachy Bellinis at Harry’s (and Hemingway’s) Bar, where the cocktail was invented, we return to our moorings, just across the St Mark’s waterfront at our loveliest mooring of all, in San Giorgio Maggiore. With its cypress-framed vistas and monastic solemnity, this island feels far removed from the commercial maelstrom over the water. Seen from afar, the austere monastery appears suspended in the inner lagoon, with its cool Palladian church matched by a bell tower modelled on St Mark’s. Together with the church of La Salute, these bold beacons guard the inner harbour of Venice. We go to bed beside this island that’s still inhabited by Benedictine monks. I am rocked to sleep by the gentle motion of our bobbing boat and dream of that haunting novella, Death in Venice: the brooding hero’s gondola glides past “slippery corners of wall, past melancholy façades reflected in the rocking water.”

The moods of the city

Morning banishes monkish apparitions and I am woken by the liquid light and the urge to climb the bell tower before the hordes arrive. The island’s aloofness from Venice makes it the best vantage point for appreciating the city’s complex pattern of canals and churches.

Curiously uplifted, I hurry back to our boat for pastries on deck with the equally sunny crew. Aided by changeable light and a capricious climate, the city is a barometer of our moods. Writer Jonathan Keates sees Venice as “the great masseuse of our hankerings and illusions: she discovers us not for what we are but for what each of us would like to be.” If so, we were unmasked as simple souls, lulled by the slow rhythms of the boat.

On our last night in Venice we perch on the pontoon at the stylish Linea d’Ombra bar on the Zattere waterfront and sip chilled dry Veneto wine while waiting for a fishy risotto. Venetians look for a rippling wave effect, all’onda, forming on the silky surface of their risotto as proof that the rice is cooked to perfection. Walking off our dinner afterwards as we head back to the boat, we are reluctant to say our farewells to the Grand Canal.

Back at our moorings we are all agreed that our unique voyage around the waterways of this haunting city will never leave us. It is as Jan Morris writes: “Wherever you go in life, you will feel somewhere over your shoulder a pink, castellated, shimmering presence, the domes and riggings and crooked pinnacles of the Serenissima.”