Florence is the perfect venue for a weekend away if you simply want to be a tourist: there’s so much to see, read about and photograph, and it’s one of those rare places where there’s really no point in trying to blend in with the natives – try to and you’ll be spotted a mile off. Fortunately, this is a tourist-friendly city.

For one thing, much of Florence beyond the wide vialli that encircles the old town is not all that attractive – it’s not ugly, it’s just non-descript; you feel you could be in the suburbs of any Mediterranean city, and not the city that gave us artistic perspective, double-entry bookkeeping, pounds, shillings and pence.

Secondly, there are plenty of Florentines who will know you’re a tourist anyway because you’re not wearing the latest Gucci, but rather last year’s cast-offs that you picked up after Milan Fashion Week from the ‘stock houses’ and outlets in and around the Mall, in Leccio (a 40-minute drive out of town if you’re ready to give the credit card a bashing). Florentines are very fashion-conscious, even by Italian standards – in fact, they get a fair bit of ribbing from their compatriots about their attention to appearance.

They love their labels and sunglasses and (I don’t think I was imagining this) I noticed some people looking disdainfully at my shoes – a perfectly acceptable pair of fairly new Birkenstocks – I suppose they just weren’t Ferragamo. Modern Florence is as much about fashion as its extraordinary museums and churches, though the Florentines take both subjects very seriously. Apparently, there was recently a big argument about how to clean Michelangelo’s David.

It was in the newspapers, on television, and every Italian had an opinion – although it never really captured the imagination of the wider world audience. Some people said wet poultices should be used on the sculpture; others advised a dry brush. The wet-wash faction won – though apparently in the 19th century they gave it an acid bath, which doesn’t seem to have done it any harm either…

The Art of Style

As well as being stylish, the Florentines know their Renaissance art and are proud to tell you stories you probably didn’t know – and perhaps wouldn’t even completely believe – about their great legacy. But you should still do your homework before you go to Florence, even if only to understand how to beat the crowds and the rip-off merchants – though if you’re going there, you’re probably going for the art and architecture, and you’ve probably already done your homework. In which case, don’t read too many guide books before you go, or you’ll come to believe that the city of the Renaissance, though beautiful and home to much of the most influential art and architecture Europe has ever produced, is a smoggy mess of thousands of cars and millions of motorini, all happily honking in the oppressive heat. (Mediterranean heat is always ‘oppressive’, especially before the summer weather breaks around ferragosto.) But it’s really not like that at all any more…

Over 10 years ago, Florence was introduced to a congestion charge in the city centre; and you cannot park there unless you live there, which, unless you’re rich or you’ve been there for decades, you don’t. This, along with the improved bus services, has eased the congestion considerably. The traffic is, admittedly, worse during the weekday rush hours, when people are in a hurry to get to work and you, with your dithering map-reading and your ill-fitting Universita’ di Firenze T-shirt, are getting in the way – though the Florentines are far too polite to mention that…

People do stop at pedestrian crossings – sometimes – and generally drive at a maximum speed of 30kph – although on one Sunday morning I did see a motorino splayed on the cobbles between a bus and a car, while locals conversed – notably placidly – about the relatively urgent need for carabinieri.

(A couple of streets later I saw said military police slowly rolling across the cobbles in a car, one of them languidly smoking a cigarette.) I saw another accident, too, again in slow traffic – no damage done. Okay, so maybe, by British standards, Florence is infested with motorini, but compared to Trafalgar Square, at least there weren’t that many pigeons in the Piazza del Duomo…

Seeing the Sights

This is a good place to start: the top of Giotto’s Campanile, with an elevated view of the city from which to orientate yourself. It also seemed natural to gain the higher ground. Long before the Renaissance, Florence had at one time more than a hundred privately built towers jutting up above the low-level skyline, where the rich lived to protect themselves and their wealth. Florence’s chequered history is an often-violent story of a trading city with no natural defences on the confluence of two rivers, surrounded by the hills from where enemy armies have amassed and condottieri have held the city to ransom.

In fact, holding the city to ransom was all the rage for a couple of hundred years, and two of the culprits – Giovanni Acuto (aka Sir John Hawkwood) and Niccolò da Tolentino – are depicted in frescoes inside the Cathedral. Hawkwood, an Essex man, arrived in 1375 with a large army and a threat to lay Tuscany waste if he were not paid huge sums of money – which he duly was, before becoming the city’s leading soldier. The next painting downstairs is Domenico di Michelino’s Dante et Suoi Mondi. It tells us that Florence expelled Dante for his political opinions, but revered the leaders of the mercenary armies that had held them to ransom…

From the top of the Campanile – and also from the top of the Duomo – you can see where the places of interest are, nestled among the terracotta roof tiles (they even have terracotta-coloured satellite dishes, to blend in, you understand). You can see the Piazza della Repubblica, Florence’s 19th century central square. You can see the bridges over the River Arno and the Franciscan church of Santa Croce. You can see the Galleria dell’Accademia. You can see the hillside town of Fiesole, which was besieged and captured in 1125. Many of its walls and buildings were destroyed, though its Romanesque cathedral was spared.

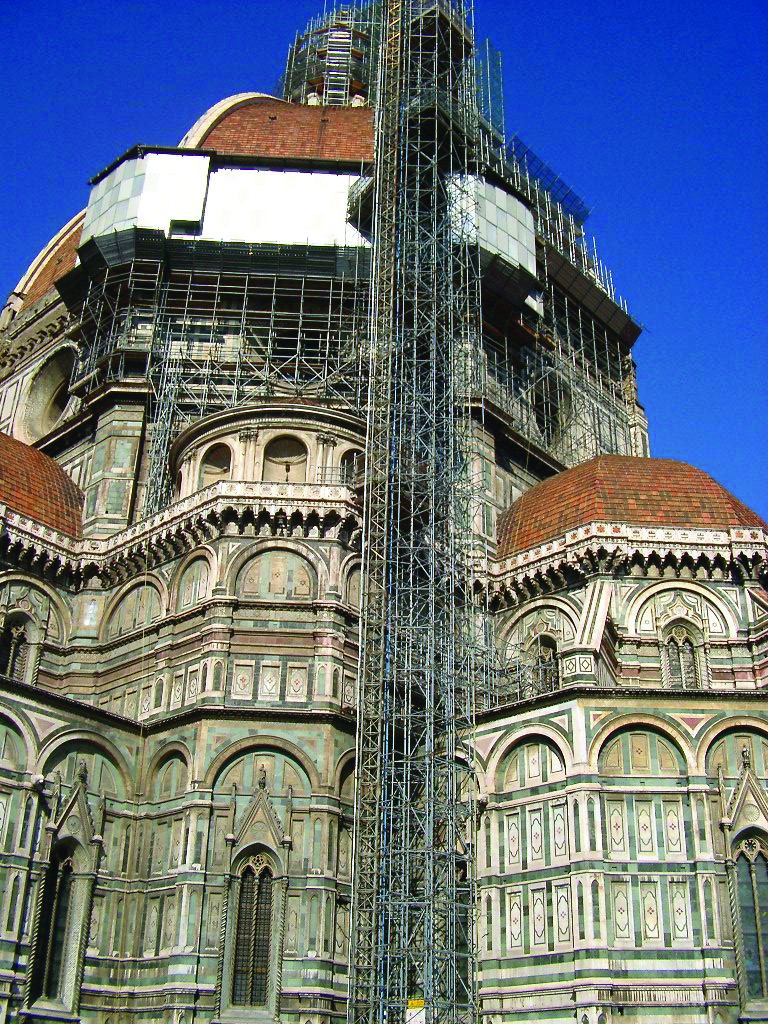

Directly opposite, so close you can make out the individual tiles, is the Duomo. Giorgio Vasari – the artist who, with Federico Zuccari, painted the interior fresco of il Giudizio Universale, which Brunelleschi did not live long enough to see – tells the story of how Brunelleschi broke an egg to explain to the committee of the Builders’Guild how he should be the one to build the Dome. Brunelleschi suggested that the job was best undertaken by the man who could make an egg stand on end. All tried – nobody succeeded.

“It’s impossible,” they said. “Not so,” Brunelleschi replied, taking the egg, smashing it on the table and standing it on its end. “But Filippo, anyone of us could have stood the egg on end if we had known you could do it like that…” the others laughed.

“And anyone would also know how to vault the cupola if he had seen my model and plans,” Brunelleschi replied, gathering his affairs and marching out of the building, on his way to work. That was the only explanation he ever really gave, so the committee of the Builders’ Guild hired Lorenzo Ghiberti to oversee the project and make sure Brunelleschi wasn’t as mad as some people thought he was.

Brunelleschi was not happy with this – he feigned illness, and when the committee sent someone to inform him that the building wasn’t going very well since he had left, he said: “Why? Isn’t Lorenzo there?” “Yes, but he can do nothing without you.” “And I would work better without him”, Brunelleschi replied before retreating to his rooms. He later worked without Ghiberti.

People from the Past

Michelangelo could be equally difficult. He worked quickly but left most of his sculptures unfinished – because he had made a mistake, because he lost interest, or perhaps because he wanted the viewer to complete the work in their mind. When people implored him to work, I was told by an educated Florentine that he used to pretend to work and, so people wouldn’t suspect him, he would occasionally just blow from a handful of dust he had secretly taken to the sculpture with him. You’ll meet these characters, and more, who live on through their work.

You’ll also meet Cosimo de’ Medici, the patron who commissioned much of the architecture of the Renaissance – there’s a statue of him on his horse in the Piazza della Signoria. As well as being the man behind the Duomo, the Grand Duke Cosimo I commissioned the Ponte Santa Trinita, considered by many to be the most beautiful bridge in the world. Cosimo, who is remembered as a benevolent and wise ruler, asked Vasari to supervise construction of the bridge; Vasari consulted Michelangelo in Rome, though much of the work is actually by Bartolommeo Ammananti.

The bridges over the Arno are all worth a closer look, though – they have all been rebuilt since the Second World War (apart from the Ponte Vecchio, which survived the war). For one thing, it’s an excuse for a riverside stroll and a view of the Oltrarno, which you’ll also want to wander around, taking your Florence maps, guidebooks and camera with you.

In fact, unless you’ve to Florence for the shopping, the only time you do not want to be seen holding a map and a book and still looking lost is when it’s

time to eat. Then you want to get as far away from the tourist track as you can. The Florentines are famously commercial – trade has always been their livelihood – and they fully appreciate the value of their city. Consequently, tourist shops and restaurants can be very expensive – and their fare mediocre at best.