We are still making discoveries at Herculaneum, and computer technology may be about to reveal something very special, says Joe Gartman…

Photos by Patricia Gartman

It’s been ten years or more since I saw the little, old-fashioned wooden display cases sitting in a deserted room of the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. When I looked into one, there wasn’t much to see. The lighting was low, and I had to stoop and peer carefully to see the small cylindrical lump of charcoal inside, about two inches in diameter and perhaps eight inches long. It rested on a small metal tray, and it seemed that someone had peeled off a thin outer layer of charcoal, unrolled it like a delicate skein of black lacework, and suspended it from the inner top of the case.

The charcoal lump was part of a collection of antiquities from an ancient villa in Herculaneum, the small resort town on the Bay of Naples that disappeared, on an August day in 79 AD, under a huge pyroclastic flow of superheated mud and gases billowing at 60 miles per hour down the slopes of Mt Vesuvius. Any inhabitants who hadn’t fled the city in time were killed instantly by the flow’s terrible heat, nearly 500 degrees centigrade. Pompeii, a few miles further south along the coast, had been buried under nine feet of hot pumice and ash a few hours earlier. The mud that covered Herculaneum, and later hardened into volcanic rock, was as much as 75 feet thick.

Treasures indeed

Trapped and preserved under Herculaneum’s stony blanket were all the inhabitants’ possessions, trash or treasure; and since Herculaneum was a popular getaway for wealthy and powerful Romans, their holiday and retirement villas often contained treasures indeed. But the town was forgotten until, in 1709, an Austrian nobleman, the Prince d’Elbeuf, heard that some well-diggers had struck statues instead of water. He bought the property around the well and hired a team of diggers to tunnel outward from the bottom of the shaft. He was lucky. The bottom of the well was in Herculaneum’s theatre, and the prince was able to lavishly decorate his villa at Portici, just north of the buried city, with fine ancient sculpture and wall paintings from the site.

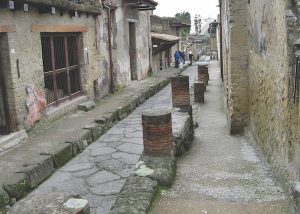

The Bourbon king Charles III of Naples followed suit, financing excavations by his Spanish military engineer, Joaquín de Alcubierre, who later discovered Pompeii. The king built a summer palace at Portici (digging up more ancient art in the process), and in 1748 ordered the creation of the Naples Archaeological Museum. Of course, many finds from Herculaneum and Pompeii found their way to the new museum. Subsequent excavations have uncovered much of Herculaneum, so that nowadays we can explore the ancient streets, houses, workshops, wine shops, and merchant storefronts; and stop at cafés with marble counters that almost seem ready to serve lunch. But the cook, alas, has been gone for 20 centuries.

Wonderful finds

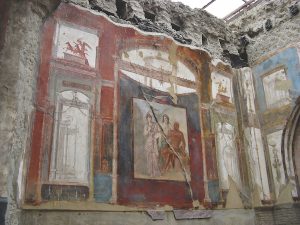

There are wonderful wall paintings and sculpture in Herculaneum and Pompeii, but to really understand the wealth of art that existed in the ancient Vesuvian cities, you must go to the Naples museum.

I was there to look at works from a luxurious villa that probably had belonged Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, whose daughter Calpurnia was Julius Caesar’s third and last wife. Piso was evidently a man of taste as well as great wealth. I saw breathtaking sculptures: five larger-than-life bronzes of the Danaïdes, mythical daughters of king Danaus, who in the underworld were condemned to carry water in a sieve for eternity as punishment for murdering their husbands on their wedding nights. You may know the story; if not, you can read it in Ovid or Pausanias. There were two startling bronze figures of young athletes, tensed to begin a race or a wrestling match, their eyes (made of ivory with black stone pupils) staring fixedly at the viewer. And many more wonderful things besides.

And then there were the lumps of charcoal. The signage around the wooden cases explained that Piso had installed an extensive library in the villa. The “books” were actually papyrus scrolls, thousands of them; and the intense heat of the pyroclastic flow had carbonized them (just as it had wooden houses, furniture, and human bones). Now the scrolls, flattened by pressure and fused together, could only be read by very slowly and carefully unrolling them and quickly copying the few characters that could be discerned before the exposed material disintegrated. Some appeared to be Greek texts on Epicurean philosophy, but the method destroyed more scrolls than it revealed, and was abandoned.

Fresh hope

But now, years later, it seems that scientists may be on the verge of reading inside the charcoal lumps without harming them, using Computerized Tomography. CT is used medically to visualize “slices” or cross-sections inside patients. If you’ve had a CT scan, you’ve been “virtually” sliced, but it is used to examine other material, too. Teams of scientists in both Italy and the United States have been testing the method, and a powerful refinement of it called X-ray phase-contrast tomography (XPCT) has shown positive results. It seems, though, that there has been considerable rivalry between the teams.

I hope they can cooperate – and hurry! There are so many lost works from antiquity; what if we could find a new play by Euripides or Aristophanes, or another discourse on science by Lucretius as wise as De rerum natura? More than 1,800 scrolls have been recovered. Who knows what may be among them? Sophocles wrote 120 plays, and we only have seven of them!

For more about other destinations in Campania, there are plenty of articles in our archive