Joe Gartman discovers that his morning coffee may require a little lift. Discover more about the history and process of making grappa today!

Images by Patricia Gartman

The swift Brenta River flows through Bassano del Grappa and is crossed by a venerable wooden bridge, the Ponte degli Alpini (which, incidentally, was designed by Andrea Palladio). At the eastern end of the bridge, in a weather-worn wall, I found a plain, grey-painted wooden door, above which was written, in old-fashioned script, Distilleria di Aquavite, Ditta B. Nardini. Well, B. Nardini, I thought, the aquavite, your ditta produces is probably grappa. And then I was struck by the thought that, despite all my Italian travels, I really knew nothing about the subject. It was time to find out. But Nardini’s wooden door was firmly locked. All was not lost, however. Using all my journalistic skills I found the Poli Grappa Museum across the street.

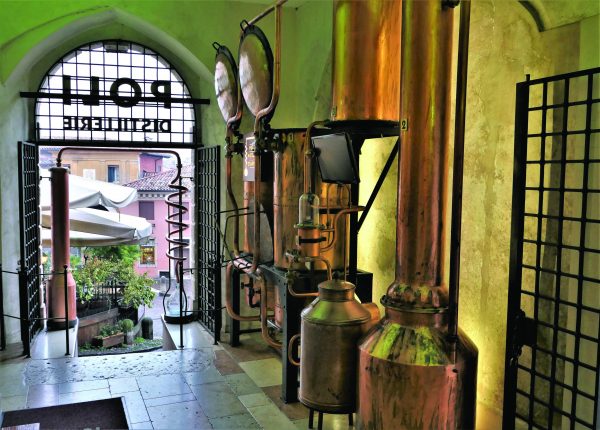

Inside the museum I found rooms full of mysterious copper vessels, pipes, pots, retorts, boilers and flasks, that reminded me a little of Dr Frankenstein’s laboratory, except shinier and more, well… multimedia. Video screens were dotted here and there, explaining the history and techniques of making grappa. Happily, I found a tasting room where, assisted by a cheerful young host named Chiara, I tried several versions of the Poli distillery’s products, which ranged from fiery to subtly smooth. Finally, armed with a handful of informational material and several sample bottles of grappa, I wound my way back to my B&B, and to quiet contemplation.

Local lore has it that back in the Middle Ages, the landowners around Bassano del Grappa were required by custom to provide a daily litre of wine for each of their field workers. They couldn’t ignore this duty, because everyone living in the shadow of Monte Grappa knew that wine was a basic necessity, just like air or sunshine; but the gentry reasoned that the peasants didn’t require really good wine.

So, after the workers picked the grapes and loaded them into the presses (they used basket presses in those days, with a stone disk at the top) the fruit was pressed, and the juice ran out between the staves into a tub, and thence into barrels for fermentation. Then a second press yielded a little more juice, bitter with tannins, that was also saved for fermentation. What was left was a desiccated mass of skins, seeds, and stems – marc, the French call it; in Italian it’s vinaccia. A perfect food for not-too-fastidious pigs, you might think. But no. The landowners saturated it with water, and if there were traces of yeast left, a little fermentation took place. After a few weeks, the liquid was drawn off and given to the farm hands. It was called vin piccolo or graspia.

Bassano and Monte Grappa are in Veneto, and winters can be cloudy and cold, so it was not very long before the workers decided that they needed something warmer and more revivifying than watery wine dregs. Perhaps some clever farm worker found himself a large pot with a lid, a length of copper pipe, a barrel for cold water, and a jug. With a pot half-full of graspia, and a fire under the pot, he could send a column of graspia vapour through the pipe, which ultimately would coil downward through the cold-water barrel. The vapours, now liquid and perhaps 80% alcohol, would then drip into the jug. It wasn’t modern grappa yet, because a 1951 law defines grappa as a spirit distilled only from vinaccia. What our hypothetical field worker produced was grape brandy, though I believe the scientific term is ‘moonshine’. But it was called grappa, and in the following centuries it was distilled and drunk throughout northeast Italy. During the First World War, it was part of the daily ration for the Alpini, the rugged Italian soldiers who fought the Austrian and German armies along the Alpine Front; Italian soldiers also drank grappa during the Second World War. Postwar, Italians have enjoyed it as a digestivo, and, added to coffee, as caffè corretto, “corrected coffee”.

One of the very earliest grappa distillers was the same B. Nardini whose closed door I’d seen at the old bridge. The distillery was founded in 1779, and, despite the rather modest door, the company produces millions of bottles of grappa per year and exports all over the world. The door marks only Nardini’s original premises. The modern distillery, I learned, is a couple of miles from the bridge, in the southern part of Bassano, housed in a large, futuristic facility; it is one of about 20 industrial-sized companies that produce nearly 80% of Italy’s grappa.

In 1898, Jacopo Poli founded the company whose museum I visited. It is still family-owned, and is one of about 100 smaller distillers who use what they call artisanal techniques to create their products. Larger distilleries use a continuous steam source to heat their vinaccia, while artisanal producers use discontinuous heating methods for smaller batches; and the artisanal distillers pride themselves on the many ways their products can be crafted. The grappa can be young, or aged in wood, steel or glass. It can be plain or flavoured with fruit or herbs. It can be made from different grape varietals. Poli even sometimes uses vinaccia from withered winter grapes, which produces a sweeter grappa.

After reading all the information from the museum, I felt a bit, shall we say, bewildered, as I went to bed that night. In the morning, I stopped at a nearby café, thinking that a strong coffee would help the slight, unexplained headache I had acquired. “I’ll have a caffè lungo,” I said. Then I thought about it. “No, wait. Make that a corretto.”

Enjoyed this article? Discover more like it in the Italia! archive.