As much as anywhere in Italy, the food of Montalcino is intensely local and dear to its residents. Wanda Djebbar explains the culinary heritage of this Tuscan town with her Gourmet guide to Montalcino…

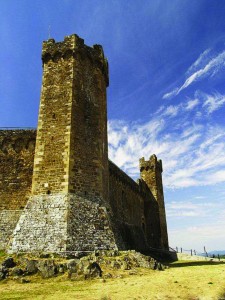

Sitting proudly on its hilltop at 567 metres above sea level, looking out over the Val d’Orcia and the Via Francigena, Montalcino was a self-governing medieval town with strong links to Siena. And Siena has always influenced its food – this much can be seen in the panforte, with its spices and nuts, and in the antico peposo spiced beef dish.

Sitting proudly on its hilltop at 567 metres above sea level, looking out over the Val d’Orcia and the Via Francigena, Montalcino was a self-governing medieval town with strong links to Siena. And Siena has always influenced its food – this much can be seen in the panforte, with its spices and nuts, and in the antico peposo spiced beef dish.

Today the town is famous for its highly respected – and expensive – Brunello di Montalcino wine, acknowledged as one of Italy’s finest, but Montalcino’s cooking has always been firmly in the cucina povera tradition. Food has been scarce at certain times in history and the people have learned to make use of every local resource possible.

As in most of Tuscany, Montalcino’s staple food is not pasta, rice or polenta, but bread. This you will still find used in many thrifty ways, particularly in soups such as the summer favourite pappa al pomodoro, bread and tomato soup, or the more autumnal ribollita, featuring cannellini beans and always served over or thickened with bread. Another staple is panzanella salad, made with soaked stale bread, tomatoes, cucumber and onion (though foraged greens can also be used). Bread, as in the rest of Tuscany, is always saltless.

In the days of sharecropping and mixed farming, right up until the 1950s that is, wheat for the daily bread was grown between rows of grapevines, until increasing mechanisation and specialisation in wine ended the practice.

Bread is the staple, but you will find two local forms of pasta: papardelle and pinci (also known as pici). Papardelle are made more rarely as they are only ever served with richer sauces, such as hare, duck or wild boar, so were reserved for feast days (or for the better off). But pinci are the essence of cucina povera, being made of flour and water, by hand, turning these simple elements into something tasty and filling. When times were hard they would have been simply dressed with breadcrumbs toasted with a little olive oil. In better times they are delicious with a summer tomato and garlic sauce, all’aglione, with a ragu, or with foraged mushrooms (cultivated ones just don’t taste the same!).

Whenever wheat flour was scarce, many at Montalcino depended on the chestnuts from the woods or from nearby Monte Amiata. Chestnuts were ground to make a flour which could be used to eke out wheat flour for bread, and which can also be made into pasta. Chestnut pasta is something that you will now find in some restaurants and can be very good indeed. Chestnut flour made a sweet treat – probably the only one the poor ever tasted regularly – castagnaccio. This unleavened ‘cake’ contains no sugar, eggs or raising agents, only naturally sweet chestnut flour, water and a little olive oil. It may have a few walnuts (or nowadays pine nuts) and maybe a few sultanas and is often finished with a sprig of rosemary. It’s a far cry from the sybaritic marron glacé that the chestnuts from Monte Amiata are often now used for!

Whenever wheat flour was scarce, many at Montalcino depended on the chestnuts from the woods or from nearby Monte Amiata. Chestnuts were ground to make a flour which could be used to eke out wheat flour for bread, and which can also be made into pasta. Chestnut pasta is something that you will now find in some restaurants and can be very good indeed. Chestnut flour made a sweet treat – probably the only one the poor ever tasted regularly – castagnaccio. This unleavened ‘cake’ contains no sugar, eggs or raising agents, only naturally sweet chestnut flour, water and a little olive oil. It may have a few walnuts (or nowadays pine nuts) and maybe a few sultanas and is often finished with a sprig of rosemary. It’s a far cry from the sybaritic marron glacé that the chestnuts from Monte Amiata are often now used for!

The fields and forests provide many of the ingredients of the Montalcino kitchen; the rest are generally provided by the orto, the vegetable garden (which would also have provided a chicken or some rabbit for the pot). These kitchen gardens are still to be found, carefully tended, even within the walls of Montalcino. They have been there since the days when marauding armies besieging the town were a regular occurrence. The orti produce the vital underpinnings of onions, celery, carrots and parsley to the kitchen, along with other favourites such as the cavolo nero, essential for ribollita, and beans of various types.

From the forest comes game: wild boar, deer and pheasant; and the equally prized fun ghi, especially the porcino. These feature on pinci, in soup and even grilled over a wood fire. Smaller wild mushrooms (or cut up porcini) often appear, bottled at home, in an antipasto. A salad of raw ovoli, wild mushrooms, dressed with a little oil is one of the simplest but most delicious starters possible. Also from the woods come two of Montalcino’s most distinctive honeys: chestnut (dark and strongly flavoured) and corbezzolo, from the beautiful strawberry tree (arbutus unedo). This honey is highly unusual, having a clear, bitter bite to it, and is excellent served with the local pecorino, sheep’s milk cheese. The rarest find in Montalcino’s woods are truffles, which do grow but are found more prolifically in the neighbouring comune of San Giovanni d’Asso. It’s not so far, if you know where to look!

ghi, especially the porcino. These feature on pinci, in soup and even grilled over a wood fire. Smaller wild mushrooms (or cut up porcini) often appear, bottled at home, in an antipasto. A salad of raw ovoli, wild mushrooms, dressed with a little oil is one of the simplest but most delicious starters possible. Also from the woods come two of Montalcino’s most distinctive honeys: chestnut (dark and strongly flavoured) and corbezzolo, from the beautiful strawberry tree (arbutus unedo). This honey is highly unusual, having a clear, bitter bite to it, and is excellent served with the local pecorino, sheep’s milk cheese. The rarest find in Montalcino’s woods are truffles, which do grow but are found more prolifically in the neighbouring comune of San Giovanni d’Asso. It’s not so far, if you know where to look!

Fields around Montalcino provide not only cultivated crops but also a wild harvest, free for the foraging! In spring a number of new wild leaves are collected to make an insalata del campo, field salad, which is served with the first eggs of the season – a celebration of spring. Even more delicious is the wild asparagus that shoots up in grass on field margins. In Montalcino this often appears in a frittata; another pairing of spring’s fresh eggs and foraged greens.

These diverse, fresh, seasonal ingredients are invariably brought together with one fundamental element: olive oil (extra-virgin always) grown on our rolling hills as it has been for millennia. It adds nourishment and outstanding flavour to every savoury dish, and even to some sweet ones. Montalcino oil (no need to specify: at Montalcino there is only one oil) is rich and complex with a slight artichoke hint and a peppery finish. Soups, stews, roasts, grills all benefit from it. Nothing beats the taste of a slice of toasted bread with the news season’s oil fresh from the press poured over it, the simplest ‘recipe’ imaginable.

Seasonal, simple and genuine, from bread enriched soups to tripe with saffron, pinci or castagnaccio, food at Montalcino is always local – and from the heart. Buon appetito!

Seasonal, simple and genuine, from bread enriched soups to tripe with saffron, pinci or castagnaccio, food at Montalcino is always local – and from the heart. Buon appetito!

GETTING THERE

By plane

Montalcino lies to the south of Siena, and the nearest international airport is Perugia, which is served by Ryanair from Stansted. Flying to Pisa or Rome would leave you with a long way to travel.