The use of stone as a medium for Western art dates back at least as far as Imperial Rome, yet it has not always found favour. Joe Gartman discovers, however, that it is alive and well in Florence…

You might be tempted to pass by. It’s just a bright little storefront in the grey façades lining Via Ricasoli in Florence, and you may instead be looking at the Duomo and the top of Giotto’s Campanile, visible at the end of the street. And even if you do glance inside the shop, you might dismiss the large picture of the Ponte Vecchio, showing the bridge lit by sunlight and reflected in the waters of the Arno. After all, such pictures are everywhere in Florence. But if you do take a second look, you’ll probably venture inside, because this picture and the dozens of others on display, are very different indeed.

You might be tempted to pass by. It’s just a bright little storefront in the grey façades lining Via Ricasoli in Florence, and you may instead be looking at the Duomo and the top of Giotto’s Campanile, visible at the end of the street. And even if you do glance inside the shop, you might dismiss the large picture of the Ponte Vecchio, showing the bridge lit by sunlight and reflected in the waters of the Arno. After all, such pictures are everywhere in Florence. But if you do take a second look, you’ll probably venture inside, because this picture and the dozens of others on display, are very different indeed.

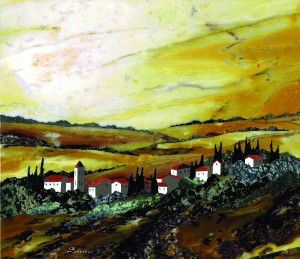

Inside, a long, rather narrow space leads back, beneath vaults supported by old, brick arches. In front are pictures: on the walls, on easels, lined up on a long marble table, or propped in corners. The large Ponte Vecchio picture stands on an easel halfway back. Close up, the pictures are even more striking. But where are the brushstrokes? What medium is being used? Not oils, nor watercolour, nor acrylic, surely. Are they painted on canvas? Paper? Wood?

Further back, under the arches, you may notice worktables lit by high-intensity lamps. And there’s a table strewn with plastic bins full of… rocks? A thin sheet of grey stone held upright in a vice is being attacked by a preoccupied gentleman wielding a strange wooden, bow-like saw. If you take another close look at the pictures, then it will hit you – they’re composed of coloured, patterned stone – slices of stone fitted together so artfully, so perfectly, that the joins disappear in the composition. The natural swirls, streaks, and shadings of colour in the stone have been so carefully chosen that they create the pictures – water, sky, buildings, clouds, even people – as if from the brush of a master painter.

Perspective, shading, modeling – all the techniques are, astonishingly, in the pictures.

Then, if you are lucky, as I was, you will meet Catia. An elegant woman with an engaging smile, she explained that her father, Renzo Scarpelli, started his bottega more than 40 years ago, after having served an apprenticeship that began when he was 13 years old. In this, he was following a tradition and an art, unique to Florence, that began with the Medici.

Florentine Commesso, sometimes called Pietre Dure work, shares its origin with other forms of artwork in stone, such as tesserae-based mosaic. But the direct ancestor of Florentine Commesso was probably the use of coloured marble to make inlays that decorated walls and pavements as far back as the imperial period of Rome. Gradually, the art fell into disuse with the end of the Western Empire. During the Renaissance, the techniques were rediscovered, or perhaps reinvented, in Florence. The Medici, most famously Lorenzo, valued beautiful objects highly, as a means of impressing fellow rulers with the sophistication of Florentine society. Inlaid decoration of colourful stonework beautified tabletops and other furniture. The images were often flowers, birds, plants, shells, butterflies and so on.

It was not until the later Medici dukes that the notion of creating portraits, landscapes, and other compositions in the manner of paintings became established. It is said that the phrase “paintings in stone” was first used by Duke Ferdinand I. He was a great patron of the arts. His appreciation of the Commesso techniques led him, in 1588, to establish the “Galleria dei Lavori” from the workshops then lodged in the Uffizi. The workshops, exclusively serving the ruling family, were supported by him and subsequent rulers of Florence, right through the end of Medici rule in 1737 and continuing under the Hapsburg Lorraine dynasty. In fact, his vision still continues today under the name “Opificio delle Pietre Dure”. The Opificio no longer creates Commesso works, but it is an important organization dedicated to the conservation and restoration of Italian art of the past.

It was not until the later Medici dukes that the notion of creating portraits, landscapes, and other compositions in the manner of paintings became established. It is said that the phrase “paintings in stone” was first used by Duke Ferdinand I. He was a great patron of the arts. His appreciation of the Commesso techniques led him, in 1588, to establish the “Galleria dei Lavori” from the workshops then lodged in the Uffizi. The workshops, exclusively serving the ruling family, were supported by him and subsequent rulers of Florence, right through the end of Medici rule in 1737 and continuing under the Hapsburg Lorraine dynasty. In fact, his vision still continues today under the name “Opificio delle Pietre Dure”. The Opificio no longer creates Commesso works, but it is an important organization dedicated to the conservation and restoration of Italian art of the past.

The Opificio also maintains a wonderful museum on Via degli Alfani, just a few streets away from the Scarpellis’ showroom in Florence. Here you can see perfectly preserved tools and devices used by the Ducal workshops, a spectacular display of coloured stones, and a stunning collection of artworks made over the centuries, when the Florentine dukes commissioned pieces to enhance the city’s reputation all over Europe. Their penchant for sending pietre dure works to impress European rulers means that today Florentine Commesso can be seen in major museums from London to Paris to St Petersburg.

Today the Dukes no longer commission masterpieces from the royal workshops, and the centuries-old tradition is carried on by master artisans like Renzo Scarpelli and his son, Leonardo. It’s a family enterprise, too: Catia looks after the business details; Renzo’s wife, Gabriella, creates unique jewellery from stone. Renzo and Leonardo employ skilled assistants – Stefano, Pierpaolo and Filippo – all of whom have years of experience. In fact, Stefano has been with Renzo for 35 years, ever since the age of 16. And a delightful young woman named Mayumi greets visitors to the showroom. Watching the whole busy enterprise, I thought that Duke Ferdinand would approve.

The dedication of Renzo and Leonardo to their art is impressive. Renzo first encountered pietre dure work as a young teenager, and despite opposition from his family, became an apprentice in one of the oldest workshops in Florence. Working afternoons as a ragazzo di bottega, (“the boy who does everything”, Catia explains), and then later helping create pieces, he spent years learning the art. At last there came a time when the maestro of the bottega told him, “I think the rest is inside you.”

Renzo met Gabriella when he was 17 and she 16. He did his military service, returned with nothing in his pockets, and went back to work in the bottega, dreaming of opening his own workshop. He and Gabriella married, and in 1972, with savings and borrowed money, started his business. At first he created pieces that were sold in other galleries, but eventually opened a showroom in central Florence.

Catia remembers that she and Leonardo used to play among the stones in the workshop. Now, she says, workplace regulations won’t allow it for her own children. Apparently, Leonardo was inspired by the atmosphere, and after years of art studies and a Master of Arts certificate, he began creating his own works in the early ‘90s. He is now an acknowledged Master of the art of Commesso in his own right.

And a very complex art it is, too. From Medici times until the present, pietre dure work has had unique requirements. One fascinating aspect is, simply, the search for raw material. Traditionally, most of the stone used in Commesso was found in the country around Florence. A special skill, that of cercatore di pietre, or “stone sourcer,” was, and remains, vital to the enterprise. In Italy, stones such as chalcedony, onyx, gabbro and many others can be found. For the artists, stones may have traditional names based upon the locales in which they are found. “Verde Arno,” is an example. Other stones, such as lapis lazuli and malachite, are imported.

And a very complex art it is, too. From Medici times until the present, pietre dure work has had unique requirements. One fascinating aspect is, simply, the search for raw material. Traditionally, most of the stone used in Commesso was found in the country around Florence. A special skill, that of cercatore di pietre, or “stone sourcer,” was, and remains, vital to the enterprise. In Italy, stones such as chalcedony, onyx, gabbro and many others can be found. For the artists, stones may have traditional names based upon the locales in which they are found. “Verde Arno,” is an example. Other stones, such as lapis lazuli and malachite, are imported.

An astonishing treasure trove of colourful rocks is stored in the cellars under the Scarpelli showroom and bottega. (I was granted special permission to visit below. It’s a workaday place, with cutting machines and tools, but a rather ghostly place, too. I felt I was stepping back in time, to the days of Duke Ferdinand’s royal workshops.)

I saw how the stones were cut into thin slices. The artists must sort through thousands of slices to find just the right colours, tonalities and patterns that match the demands of the work they are creating. Once selected, the required pieces are carefully cut (using the traditional bow of chestnut wood with an iron “string” continually moistened by a mixture of water and abrasive). Then they’re assembled together with an adhesive of beeswax and resin. Normally the image is glued to a substrate of slate, and carefully polished. The care, precision, and perfect artistic judgement involved is astonishing, and so are the results.

There are just a few workshops continuing this historic and traditional form of decorative art. Le Pietre nell’ Arte, the Scarpelli’s workshop and gallery, is unique in that you can simply admire or purchase the works displayed in the gallery, or you can watch the whole process in a working laboratorio in the rear of the shop. Catia says that they were fortunate to find the space (a former 13th century stable, beautifully restored for its present use), because there were unexpected rooms beneath street level they could use to store their huge stock of “beautiful stones”. Opened in 2008, it is the culmination of Renzo’s dream of the perfect place to create art.

Renzo and Leonardo craft pieces of their own design, but the bottega does restoration work, and custom pieces as well, which is in the historic Commesso tradition. One very large tabletop took years to create and cost hundreds of thousands of euros. They have had many other interesting commissions – one American customer owned a koi fish named Jeff, and ordered Jeff’s portrait in stone. Another request, one they could not accept, was from a motorcycle-racing fan who wanted a picture of Valentino Rossi on a shiny red racing bike. Unfortunately, there is no natural stone containing the red colour of Rossi’s machine, and the workshop declines to use any but natural materials. Many customers want their favourite painting replicated in stone, which is reminiscent of the days when the Dukes would have their court artists make paintings specifically to be turned into Commesso. One client couple from New York visits Florence four times a year to order copies of their favourite paintings, often pictures by Matisse.

A visit to the Scarpelli’s Le Pietre nell’Arte, and then a fascinating tour of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure museum nearby, will introduce you to an amazing world of beauty and history. So go ahead – step through the door of the bright little storefront in Via Ricasoli. It’s number 59/r. Say hello to Mayumi and Catia. You may meet Leonardo, too, or even Renzo himself. And if you hear some strange rattling sounds from the cellars, maybe it’s because Duke Ferdinand is still down there, looking up through all the beautiful stones.

A visit to the Scarpelli’s Le Pietre nell’Arte, and then a fascinating tour of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure museum nearby, will introduce you to an amazing world of beauty and history. So go ahead – step through the door of the bright little storefront in Via Ricasoli. It’s number 59/r. Say hello to Mayumi and Catia. You may meet Leonardo, too, or even Renzo himself. And if you hear some strange rattling sounds from the cellars, maybe it’s because Duke Ferdinand is still down there, looking up through all the beautiful stones.

INFORMATION

➤ LE PIETRE NELL’ARTE

Via Ricasoli 59/r, 50122 Firenze

+39 055 212587

www.scarpellimosaici.it

➤ OPIFICIO DELLE PIETRE DURE

Via degli Alfani 78, 50121 Firenze

+39 055 265111

www.opificiodellepietredure.it

➤ PITTI MOSAICI

Piazza dei Pitti 23-24/r, 50125 Firenze

+39 055 267 8730

www.pittimosaici.com

➤ LA BOTTEGA DEL MOSAICO

Via Guicciardini 126/r, 50125 Firenze

+39 055 210718

www.bottegadelmosaico.com

Photographs © Catia Scarpelli and Pat Garman