It would take Titian the generation following Giovanni Bellini to really exploit the full potential of oil. He digested the expertise of Bellini and then took it to another level.

Titian (Tiziano in Italian) was one of the greatest painters Venice ever produced – perhaps the greatest painter Venice ever produced. He was the first truly international European superstar artist. During his very long life (he died in his mid-90s) he worked for the Duke of Ferrara, the Dukes of Urbino, the Medici in Florence, the Popes, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and the King of Spain, Philip II. He was knighted by the Emperor (he became a Knight of the Golden Spur), he received various stipends from international leaders (he was a shrewd businessman too), and for almost 60 years he held the title of Official Painter of the Venetian Republic.

As an artist he was innovative, imaginative and a true colour engineer. At an early age, in the beginning of the 1500s, he was an apprentice under Giovanni Bellini, who headed the most important workshop in Venice at the time and was himself then the Official Painter of Venice. Giovanni Bellini had learned the oil technique from the Sicilian Antonello da Messina, who in turn had learned it from northern European painting. Antonello had lived just over a year in Venice during the mid-1470s and introduced the oil technique to the Venetian artists. Bellini, already a master painter producing beautiful work in egg tempera, had recognised immediately the possibilities of oil and, being innovative and receptive to change, he dedicated himself to exploring its potential.

Bellini became a master of glazing (the layering of colour, possible only when the pigment is mixed with oil), and he achieved a translucency and luminosity of colour that had been simply impossible in egg tempera painting. He would build up possibly dozens of extremely thin layers of the same colour (like panes of glass) in slightly differing shades, creating a prism-like effect on the surface with the pigment. The light would enter the layers of the paint and bounce off the white ground surface and return back. The end result was a deep inner colour glow from within the very image itself. This was especially effective when depicting the blue robe of the Virgin Mary or a gold mosaic apse in the background.

It would take Titian, however, the following generation to really exploit the full potential of oil. He digested the expertise of Bellini and then took it to another level. Bellini had experimented with luminosity but remained for the most part within the contours of the outline of the drawing from the traditional Renaissance detailed preliminary drawing executed beforehand. Titian, however, was the first to free up painting entirely from any formal hierarchic planning of the painting. As the oil medium was slow drying, unlike with egg tempera, he could be innovative and spontaneous directly onto the canvas and build up the surface, creating volume and atmosphere with differing surface texture and manipulation of hues, because there was room to rework and change anything that was done.

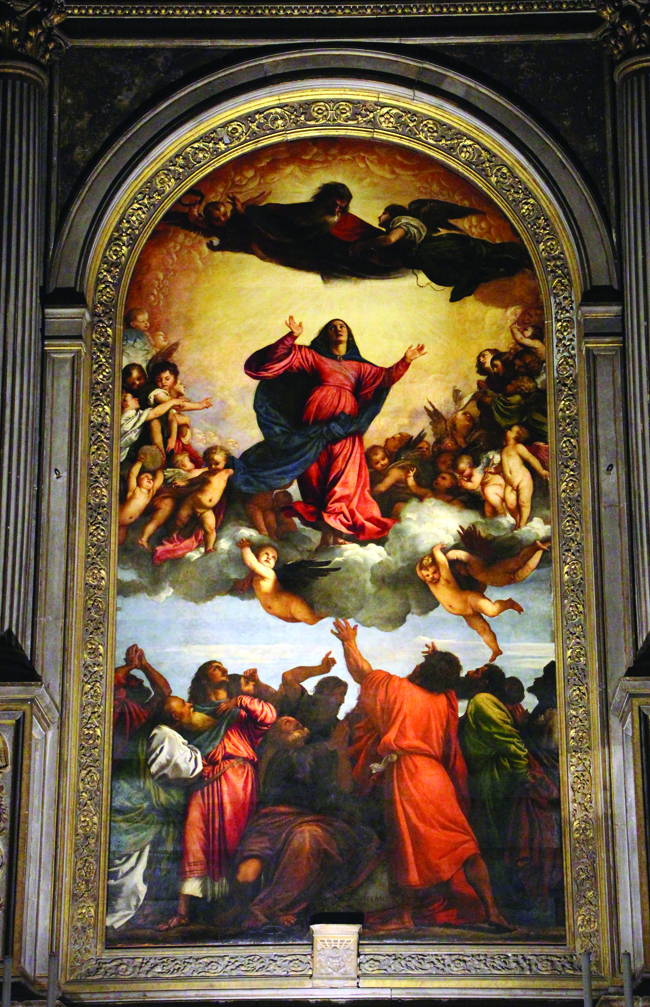

The basic unit of tempera painting had been line, and the essence of oil painting was surface and atmosphere. Line and drawing (disegno) was the basis of the Florentine artistic school and they maintained that excellent draughtsmanship was the only way to best represent nature, movement and anatomy. The basis of the Venetian school was colour (colorito) and they believed that the pulse of life and the true nature of the world was best expressed in art through the ability to utilise colour and light. Titian was the great innovator of the painterly style; no other had ever used brush strokes and colour with such mastery to convey action, power, emotion and sensuality. Whether it was flesh in his female allegories and mythological paintings or portraiture or religious paintings, Titian’s genius was his capacity to convey the very mood of the painting through colour.

By Freya Middleton (www.freyasflorence.com)