Sarah Lane travels to Italy’s northwestern corner to Aosta and discovers beautiful scenery and some surprising saints in an area of castles and culture much loved by popes and kings

With spectacular alpine skylines, a chain of medieval castles and colourful ancient customs, the Valle d’Aosta region – Italy’s smallest – has a lot to offer. Aosta itself, the regional capital, is sometimes referred to as the Rome of the Alps as the city is rich in Roman remains. Being at the centre and widest point of the Dora Baltea river valley, surrounded by some of Europe’s highest mountains, also makes Aosta an excellent base for exploring the area. This strategic position with nearby borders leading to France and Switzerland has been fundamental throughout history, and the city has been an important one since long before the ancient Romans came onto the scene.

My partner Malaga and I visited Aosta one weekend in late summer and as we approached after a long journey we were thrilled to see the picturesque peaks in the distance – several over 4,000m asl – glimmering white with freshly fallen snow. With a change in architecture to more typically rustic mountain styles, a rapid succession of fairy-tale castles and terrace after terrace of cultivated vines, the area presents itself well, with an appealing character of its own.

Parking the car at the edge of Aosta’s compact centre, near the ancient Roman Arch, Arco d’Augusto, we went in search of a snack. Strolling down the pedestrianised main street, Via Sant’Anselmo, the aroma from shops selling all sorts of cheeses and other traditional local produce helped whet our appetites. We stopped to look up at the plaque on the large grey house, which was supposedly the home of Sant’Anselmo himself. Born in Aosta in the 11th century, the saint-to-be later moved to England where he became Archbishop of Canterbury.

Not far from Sant’Anselmo’s house we found La Vineria, a shop selling wine by the bottle and a wine bar with a small, secluded courtyard where snacks and wines are served all day. Each item on the wooden platters – a mixture of local cheeses and meats – was explained to us, including the correct order from mild to strong for the six delicious and unusual cheeses. I liked the pungent blue and the different varieties of tasty toma cheese, while Malaga’s selection of meats included thin slices of a local speciality, the aromatic lard from nearby Arnad, and a curious deep red salami, coloured with beetroot.

Foreign influences

Postponing all serious sight-seeing to the following day, we took in the relaxed atmosphere of the city centre, the pretty backstreets and alleys, and the impressive array of woodwork and other local crafts on sale in the centre’s gift shops. One peculiarity of the region is its bilingual status. Both French and Italian are official languages here, taught in schools and used seemingly randomly on signs and noticeboards. In shops and bars, if you don’t seem to understand Italian, the chances are you’ll be offered French, although, used to switching languages, many locals seem to be proficient in English too. The unusual local dialect, or patois, is uncommon in Aosta itself, but frequently spoken in many of the outlying villages.

Waking up next morning to find the scenery had been spruced up by another fresh fall of snow on the surrounding peaks, we set off to discover more about Aosta and its ancient Roman pedigree, starting once again at the Arco d’Augusto. This was built to honour the long-awaited victory of the Romans over the previous local dwellers, a Celtic group called Salassi, after a war that had lasted some 75 years. The Salassi had been keen to hang onto their alpine stronghold, but the Romans were finally able to found Augusta Praetoria, as it was then known, in 25BC. At that time this triumphal arch was way out of the town centre, which was built to a fixed rectangular grid plan as was the Roman way.

Porta Praetoria, a couple of hundred metres further on, marked the real entry into town, and this impressive double gateway still stands today, the only one of the four original gates that remains.

Given the importance of relaxation and entertainment to the ancient Romans, the town had a theatre, an amphitheatre and a spa. The latter two are hidden under more recent buildings, but parts of the theatre are still standing. The stage area has a stunning natural backdrop provided by the Gran Combin mountain (4,363m) which must have played an important role in deciding which direction to face the seating. Many parts of the city walls can still be seen here and there, and seven of the original 20 watchtowers remain. Most of these were, however, altered into private residences in the Middle Ages.

Augusta Praetoria’s main forum was a grand affair, with two temples and an ambitious double gallery, the cryptoporticus, around the edge. Today, the cathedral stands on one side of the former forum, while the entrance to the underground gallery of the cryptoporticus is to the left of the cathedral. In the spacious covered gallery, which was probably used just for strolling around and chatting, you can really imagine the ancient Romans doing just that.

Saintly pursuits

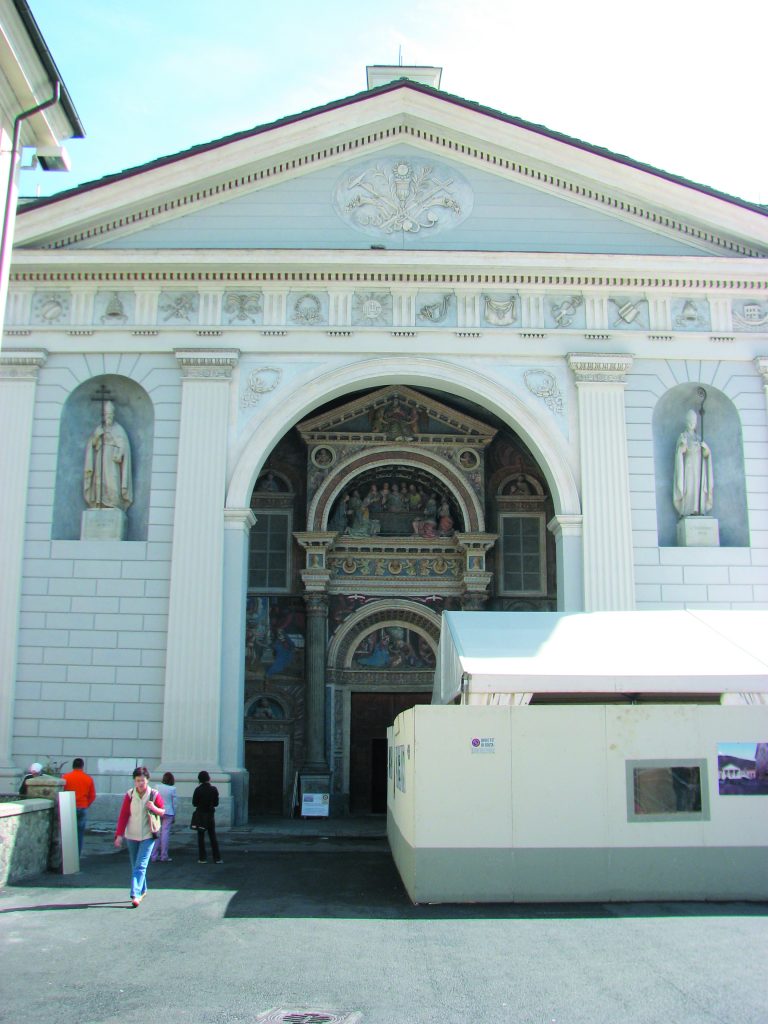

The cathedral, originally built for Sant’Anselmo when he was bishop here in the 11th century, is definitely worth a look. One saint whose influence is far more noticeable around here than either Sant’Anselmo or the local patron, San Grato, is Sant’Orso. He lived in the seventh century and is attributed with all sorts of worthy deeds, including healing the sick and reclaiming swamped land. A lover of nature, he is always depicted with a bird on his shoulder.

No doubt the main influence attributed to the saint, however, is the introduction of wood carving to the area. He apparently taught the craft to the people of Aosta and is also said to have distributed characteristic wooden clogs, or sabots, to the poor. In honour of this, the lively Fiera di Sant’Orso is held each year (30-31 January). Thousands come from near and far to see the stalls selling local crafts and the stall holders are lucky in that buying an item from the festival is said to bring good luck for the year to come.

The most symbolic item is the grolla – a large wooden wine goblet with a lid, which was passed round on special occasions in medieval times. The more intricate the decorations, the more prestigious the family. The term grolla is often erroneously used for another drinking vessel commonly used even today – the coppa dell’amicizia or friendship cup. This looks rather more like a teapot with a selection of spouts and it’s used for making Valle d’Aosta coffee – a strong brew made with grappa and orange and lemon peel, which is passed around among friends. Sharing a drink in one of these is supposed to symbolise true friendship – try one in any of Aosta’s bars.

Opposite the church of Sant’Orso, in the medieval part of town not far from the Arco d’Augusto, stands a lime tree over 450 years old. Split in two by lightning half a century ago, the sturdy tree continues to thrive. The church, like the cathedral, dates from the 11th century and, with a number of interesting features, it’s one of the city’s main sights. Down in the crypt take a look at the gap beneath the altar – the grooves on the floor are from the knees of believers who would squeeze through in the hope that their backache or other ailments would be healed. The church and the nearby cathedral underwent alterations in the 15th century when Giorgio Challant, a member of the local noble family, was Prior of Sant’Orso. He had the ceilings lowered and frescoes can be seen in the spaces between the current and original ceilings. He also left his mark on several of the area’s castles, such as Fénis and Issogne.

Storming the ramparts

Of the castles we visited, Issogne left most of an impression. Although fairly unassuming from the outside, the interior is just how a medieval castle should be, with huge fireplaces and chunky wooden furniture. The 19th-century artist, Vittorio Avondo, bought the castle and restored it with original pieces and faithful reproductions, returning it to its medieval self before opening to the public. The structure has remained unaltered since Giorgio Challant’s day and many original frescoes are amazingly well preserved. A wrought iron pomegranate tree has stood in the courtyard for hundreds of years, since it was presented by Giorgio as a wedding gift to his nephew, Filberto, heir to the family title.

Another memorable castle, a bit nearer to Aosta, is Sarre. Originally built in the 12th century, the castle was bought in 1869 by Vittorio Emanuele II, the first king of unified Italy, when his attempts to buy the castle at Aymavilles across the valley came to nothing. Nowadays, the castle interior is dedicated to the time of the king and the other Savoys. Vittorio Emanuele II used it as a hunting lodge and two halls on the first floor are decorated with a collection of horns – over 3,600 altogether – from ibexes and other animals he hunted. Classical music concerts are held in this unusual environment, while open-air rock concerts take place in the castle grounds each summer.

Vittorio Emanuele II loved the Aosta region and thanks to his donation of the land, the Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy’s first, came into existence in 1922. The park, which stretches south into the Piedmont region, is a wonderful area of natural beauty where ibexes – the park’s symbol – and other mountain wildlife, such as chamois goats and furry marmots, roam. Pope John Paul II chose to come here for a decade of summer holidays, staying at Introd, and his successor, Benedict XVI, has continued the tradition.

Into the mountains

On our last day in the area we made one more trip out of town, taking the cable car from central Aosta up to Pila. The trip up takes about 18 minutes and moves swiftly and steeply so you get terrific views over Aosta below. In front and behind us on the cable car were mountain bikers, as Pila is a well known MTB venue, and world-class events are held here. There are plenty of bike paths to choose from – it’s not just for those with the skill or daring to face the most challenging runs. Pila itself is a newish winter and summer mountain resort and you’ll find a varied selection of bars, restaurants and hotels. We were heading higher, though, and took the chairlift to Chamolé where the delightful Baraka bar refuge tempts all those arriving from the chairlift. We allowed ourselves to be tempted and enjoyed a relaxing half hour taking in the view from the panoramic terrace, trying to identify the multitude of peaks to be seen in all directions.

There’s a good choice of footpath from here, but, running out of time, we headed downhill back to Pila. Although we had a map with us and had asked for tips on the best route, the paths we aimed to take seemed pretty much unmarked. But the general direction was clear and we bumped into a couple of other sets of people studying their maps intently when there was a choice of path. We all chose different directions and our path took us past a group of beaver-like marmots out enjoying the sunshine. After eyeing each other up for several minutes, we and the furry creatures went our separate ways.

With just enough time to have one last stroll through Aosta’s pedestrianised centre, and to buy ourselves a friendship cup, we took our leave of the city, wishing we had a few more days to spend here. Aosta makes a great base for exploring the beautiful region, and the city itself is terrific and has some stunning views – just as the ancient Romans realised over 2,000 years ago. n!