Follow Marina Spironetti as she discovers the western area of the Bay of Naples, retracing her ancestoral Roman footsteps –with history, legends and the volcano’s own curiosity shop…

As soon as I step into my room at the Hotel Parker’s, in Naples’ stylish Vomero district, I head towards the window. I quickly open the blinds and step onto the balcony, overcome by the intense late morning light. In front of me is the postcard pretty view of the city, with the imposing Vesuvius in the background – a familiar sight I will never get tired of. Beyond is Sorrento and its luscious peninsula, and Capri is only a short ferry ride away. This time, however, I am exploring the western side of the Bay of Naples, a region known since the ancient Greeks as the Campi Flegrei – the fiery fields.

As soon as I step into my room at the Hotel Parker’s, in Naples’ stylish Vomero district, I head towards the window. I quickly open the blinds and step onto the balcony, overcome by the intense late morning light. In front of me is the postcard pretty view of the city, with the imposing Vesuvius in the background – a familiar sight I will never get tired of. Beyond is Sorrento and its luscious peninsula, and Capri is only a short ferry ride away. This time, however, I am exploring the western side of the Bay of Naples, a region known since the ancient Greeks as the Campi Flegrei – the fiery fields.

The name could not be more appropriate, for this is really one of the most unstable corners of Planet Earth. The area is known for its continuous rising and sinking landscapes – a bizarre phenomenon known to geologists as bradyseism – sulphurous pools, thermal springs and some 40 volcanoes, some of which are even able to appear overnight. This was what happened with Monte Nuovo back in 1538. As if mighty Vesuvius was not enough! Although mass tourism hasn’t arrived yet – and perhaps it won’t for a while longer – this was the California of the Roman world: fertile, sun-drenched and with glitzy resorts lined along its spectacular coastline.

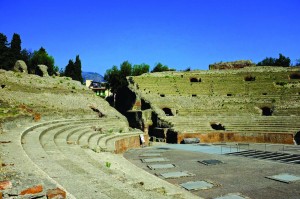

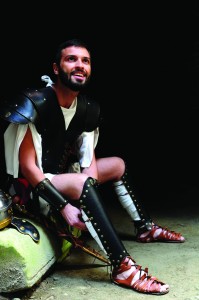

The coastal road leaving Naples passes through the suburbs of the city, running along the tiny island of Nisida, a dead volcano where allegedly Brutus and Cassius planned Caesar’s murder, and takes me to Pozzuoli, the first stop of my time-journey. Nowadays a rather ordinary town, famous mostly for being Sophia Loren’s birthplace, in ancient times Roman Puteoli, not Naples, was the metropolis of the Bay. No wonder Nero and Vespasian endowed it with a first-class amphitheatre, the third-largest in the Roman world, after Rome and Capua, fit for some 40,000 excited spectators. The true surprise lies underground, among the impressive vaults that are probably the world’s best preserved. When I visit, there is a theatrical re-enactment going on: soldiers, merchants and prostitutes rove under the imposing brick arches. The atmosphere is dense with history –

I feel like I almost have to kick those ghosts away.

A WORLD UNDERNEATH

A WORLD UNDERNEATH

The other surprise is the Rione Terra, near the harbour, which has been the beating heart of the city since Greek times. The slow, bradyseismic earthquakes caused a progressive subsidence of the area, which was eventually abandoned in the 1970s.

It is a deserted, eerie 17th-century quarter, dominated by the ancient temple of Augustus – a quintessence of elegance, which instantly reminds me of the classical architecture of the Maison Carrée in Nimes.

Still – another world awaits underneath, a fascinating urban stratification 10-15m below the ground. A large, ongoing excavation and restoration campaign begun in the early 1990s has uncovered a virtually intact Roman town, like an underground Pompeii. Along the main decumano (the central avenue running east to west) and some minor streets are shops, taverns, a pistrinum (mill), and the unmissable lupanare, the brothel.

It really feels like one has to venture underground to understand the true essence of this restless land. Or underwater, like in the case of the Roman city of Baia. Now a small fishing town dominated by the fortress-like Castello Aragonese – which has been converted into an archaeological museum – it once was an opulent seaside resort. Any prominent patrician would have a villa with a sea view here, completed with a few hundred slaves to dust the statues and clean up after the wild bacchanalia parties.

The city of the Dolce Vita turned into a Roman Atlantis, a victim of bradyseism. To catch a glimpse of such a unique archaeological area, I embark on a glass-bottomed boat (I decide I am not brave enough for the scuba diving tour) that should allow me to spot the ruins. The guide and the sailors discuss the weather: it appears that it’s not the best. Still, we decide to give it a go and we are allowed into the bottom part of the craft. There is an otherworldly blue light as we move slowly along the streets of the ancient city, among the underwater vegetation. Structures have been excavated and roped off, and the guide seems to know exactly what is where – sadly, the weather is not good enough. I can only discern a statue – a marble arm, a face – which quickly disappears.

A MAGICAL ENCOUNTER

A MAGICAL ENCOUNTER

After going underground and underwater, it feels like only the descent into hell is missing, and Lake Averno might be the right place to do so. One of the four lakes of the Campi Flegrei, this was once supposed to be the mouth of hell. Its name is ancient Greek for ‘no birds’ and it is believed that any passing animal would be killed by the infernal fumes (or, simply, sulphurous vapours) rising from it.

From the lake shore it is only a short walk to one of the area’s most atmospheric sites, the Antro della Sibilla Cumana – the cave of the Cumaean Sibyl. According to one interpretation, this was the setting of Aeneas’ encounter with the priestess to the god Apollo, who leads him into the underworld, as described in Virgil’s Aeneid.

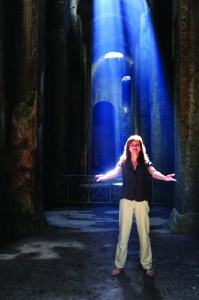

More likely to have been an underground military trench, it is still a place of mystery. We are all given a torch to enter the long trapezoidal corridor cut out of solid rock. Our eighty-something guide makes the visit all the more interesting. He’s been there ever since the grotto was opened and he’s got plenty of anecdotes to tell. At the end of the cave, a grotto marks the spot where the Sibyl would inhale fumes over the ceremonial tripod, chew laurel leaves and go into a trance. We are asked to take a seat, and we can barely see anything at first. Then the actors come out, re-enacting the mythical encounter from the Aeneid. It was one of the most intense theatrical performances I have ever seen, and one I won’t easily forget.

LASTING MEMORIES

Still, it is refreshing to be in the open air again. The last stop on my itinerary is the Piscina Mirabilis, near Bacoli, the greatest water reservoir ever built in Roman times. It was the final point of the Aqua Augusta, the impressive Augustan aqueduct that brought water to Naples, the Phlegrean Fields and Pompeii along a 100km route.

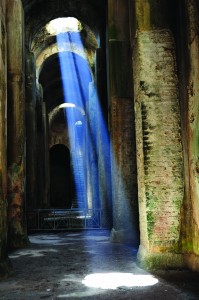

Entirely excavated in the local tufa stone, its numbers are truly impressive: 15m high, 72m long and 25m wide, with a barrel vault supported by 48 enormous cruciform pillars, set in four lanes to form five long naves. All this to contain 12,6000m3 of water. As I descend the stairs, my first impression is one of awe. A pagan cathedral where water has been replaced by sunlight.

A mystical place, incredibly survived to centuries of bradyseisms and earthquakes. A little miracle.

Planning to explore beyond Naples and visiting the Campi Flegrei? Click here for top tips from where to dine, where to stay and what to see and do!

Images © Marina Spironetti