In the second part of our six-part series, Jon Palmer continues on the trail of the Grand Tourists by chasing after a few sedan chairs around 18th-century Turin, Genoa and Milan.

Few considered Turin an important destination on their Grand Tour. It just happened to be the first city you came to. Back then, anyone who had an education had a classical education. It was the antiquities of Rome that the tourist had really come to see. Turin, delightful though it was, was really just a friendly stop-off point where one could relax after the rigours of the chair ride down the mountains.

Italy, however, is full of antiquity and the tourist’s first encounter with it lay right there on the road to Turin: the Triumphal Arch at Susa, erected

in honour of the Emperor Augustus some 2,500 years before. John Holyrod was “delighted with its beauty and fine proportion”, as he was by the “extremely magnificent” approach to Turin: “There are no suburbs in that part of the town where we entered,” he noted.

It was a good thing that there were no suburbs, because those would have been just the sort of places where common people might lurk, all dressed in brown rags and with teeth missing. The land of Piedmont was rich and fertile, but enlightened ideas such as land reform had not yet reached even this far into Italy and the people of the country were desperately poor. The king taxed his subjects brutally. “He draws from the hands of the peasant every farthing which the ingenuity of the farmers of revenue can find means to extort,” to quote one visitor. Consequently, the city of Turin was as opulent as the road that led to it promised it to be.

It hadn’t always been thus. After considerable trouble with the French during the 17th century, Piedmont eventually succumbed to being annexed to the Duchy of Savoy in 1713 – a consequence of the treaty that ended the War of the Spanish Succession. The unusually long period of peace that followed meant that the rebuilding of Turin, which had begun during the previous century, could now be completed.

The architect Filippo Juvarra was commissioned for the job. But it wasn’t only the cityscape that was constantly changing: the throne room needed redecorating every few years or so, too. The new king, Victor Amadeus II, a keen militarist and a staunch ally of Great Britain, was also still the Duke of Savoy, and King of Sicily – or at least he was until 1720, when Savoy swapped Sicily for Sardinia, at which point he became the King of Sardinia.

Musical thrones

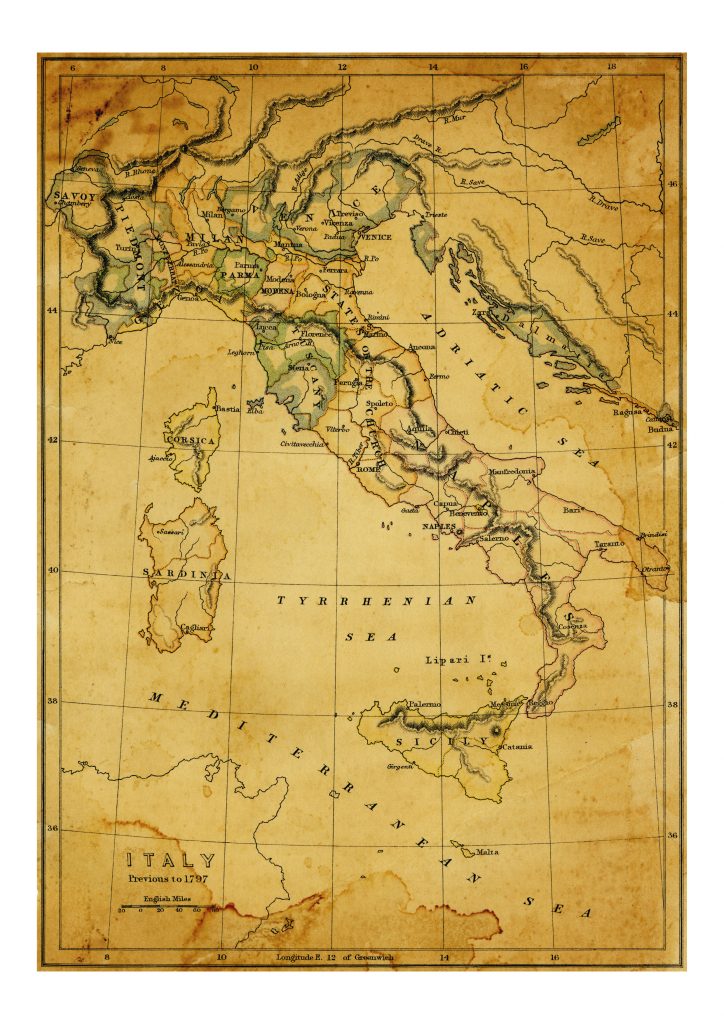

All this sounds complicated – and indeed it is, unnecessarily so – but such games of musical thrones were not uncommon in 18th-century Italy. The balance of power in Europe was held between France and Austria. The small states of Italy were often perceived as little more than convenient places for disposed royalty to be shipped out to when their usefulness had come to an end. This meant that the map of Italy was constantly evolving. It wasn’t until the end of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748 that its borders and rulers settled down enough to make a career in cartography not seem utterly futile. And then, of course, it all kicked off again in 1796 when Napoleon led his first campaign into Piedmont. However, when there wasn’t a war on, Turin was a very nice place to be – providing, of course, one was of noble birth.

The city did not have the classical riches of the Papal States and the Kingdom of Naples. Neither did it have the culture and society to be found at Florence, nor the exotic allure of Venice, but it did have a lot to offer beyond life at court. For the British aristocrat, it was a gentle introduction to the peninsula. At the end of most of its rectilinear patterned streets, one could see the Alps, views that lent the town the sense of urbs in rure it shared with Genoa and Florence.

Of course, even after its rebuilding, Turin was no Paris or London – it didn’t even compare particularly favourably to Munich or Vienna – but at least it had sewers, unlike Verona, for example; proper accommodation, unlike much of the rural Appenines; and proper roads, unlike much of the Papal States, the Kingdom of Naples, and pretty much all of Sicily outside Palermo. Later in the century it even had English plates to dine off, rather than the ubiquitous earthenware of the rest of Italy. And its picturesque situation was commented upon by many.

Most British visitors enjoyed their stay in this most European of cities, either because of or in spite of the constant effusive bowing, the going to prayers – several times a day – and the interminable carriage rides that were the principal amusements of its aristocracy. Furthermore, Turin had a fine academy, a sort of finishing school where young men could be taught to appreciate the finer things in life. The academy was relatively inexpensive too, although many of its pupils still managed to rack up the costs to mater and pater with fancy clothes, equipages with running footmen, and a chair following them about everywhere they went, just in case they came to any inconvenient steps.

The places to visit with one’s entourage were the king’s palace and hunting lodge, the groundbreaking Teatro Regio and the brand-new Church of the Superga, from where one could see the River Po cutting its course from the mountains to the plains and, even on a clear day, as far as Milan and the Appenines.

The treasures of Genoa

To see the sea, however, and to hire a felucca to sail to Leghorn, if one was heading directly for Rome, one had to ride to Genoa.

Although it was a much more compact city, there were more ancient treasures to see in Genoa than there were in Turin – and the beef was reckoned to be more tender because the cattle had been softened up by the drive over rough terrain from the north. Arriving in summer one was met by “roses, carnations, jessamines and flowers of every hue in vast abundance in every street”.

But although the Mediterranean flora impressed visitors, Genoa had one major drawback for an aristocrat: it was a republic, not a monarchy. This meant there was no court to be presented to and also that bowing opportunities were at a premium. For a down-to-earth man like our friend John Holyrod, this actually came as something of a relief – he had become tired in Turin of having to bow to people of note each and every time he met them – although to a couple of young gentlemen such as the often ebullient Charles Abbott and his more laconic touring partner Hugh Leycester, this lack of courtesy, and indeed the very foreignness of Genoa, was disconcerting. For not only did the Genoese take great pride in their flower displays, they had also developed the distasteful habit of painting their houses in bright colours. Charles greatly enjoyed “the magnificence of its natural situation, and the great abundance of immense palaces constructed upon a scale of grandeur unknown in other cities”, but was highly critical of what the locals had done to the beautiful buildings of Gènes le Superbe.

“To see green, blue and strawberry coloured walls,” he wrote, “shocks at first sight. And with reason, as those colours resemble nothing that properly belongs to any known materials for the construction of buildings.” Neither was young Master Abbott impressed by “the painting of palaces with columns, cornices and entablatures in imitation of real architecture”. Or the heat. He and his friend soon developed the clever tactic of only walking about at night, preferring during the daytime to be carried about in their chairs.

But it was the Genoese people themselves who came in for the most criticism from foreign visitors. Genoa was considered a lawless place, populated principally by extortioners and insufferably ugly women. “If they go to reckon any money or cast up a sum,” wrote Edward Thomas, “they are sure to make a mistake to their own advantage.”

“The generality of the women here are the most ugly hags in the universe,” opined the Reverend John Swinton, the old charmer. “Their heads are of a monstrous size,” he continued, unabashed. “Their complexion swarthy and olive-coloured, their features large and their mouths exceeding wide.” And in conclusion: “I imagine myself in the land of the Gorgons.”

And so to Milan

Such were but a few of the perils that faced John Holyrod as his felucca sailed out of the port of Genoa. Better for us now that we stay in the north and make our way across to Milan “through the finest country which can be seen, full of corn, wine and oil, all of which would be exceeding cheap,” reckoned one tourist, “were it not for the little Dukes and the Emperor”.

The other noticeable aspect of the countryside of the Milanese, apart from its fecundity, was the many fortifications that had been built to its towns. Lombardy had been conquered by Austria during the War of the Spanish Succession and was now subject to Habsburg rule under Emperor Charles VI. Apart from his city walls projects, the Emperor had an army of 30,000 men and the taxes levied to sustain this force were high. This made the journey interesting for those of a military bent, although there wasn’t really much for the Grand Tourist to do in Milan, except go to the opera. The British aristocracy liked the opera, or at least opera seria, because they saw that it sought to recreate the theatre of antiquity.

Many a tour was diverted to Milan to include a performance. The city was only just beginning to emerge as the economic powerhouse of Italy, but the opera was very good, especially if the Galli-Bibiena family had designed the set. Theirs was the most extravagant scenery of all, and the Habsburgs were their best patrons. Furthermore, Milan had the attraction that it was on the way to Venice, which also happens to be where we’re headed next.