The second part in the series, click here for part 1 of Hidden Rome

Previously, we visited one of the earliest surviving Christian ruins in Rome and Nero’s summer residence, Domus Aurea. This week we relax in the open spaces at the Diocletian baths and investigate the the mysterious and tragic stories behind the tombstones at Campo Cestio, the Old Cemetery for Non-Catholic Foreigners.

Diocletian baths and Santa Maria Deli Angeli e dei Martiri

Part of the Museo Nazionale Roman

Diocletian baths and Santa Maria Deli Angeli e dei Martiri is where you can get your fix of gardens, Roman ruins and churches all in one exquisite extended complex. If you don’t have the energy or time to go and traipse round the Vatican or Capitoline museums, the Baths of Diocletian are the perfect alternative. Built between 298 and 306 AD, they were the largest thermal construction ever built in Roman times, able to accommodate up to 3,000 people in a pool measuring 4,000 square metres.

This surprisingly peaceful compound is made up of The Baths, The Certosa (Charterhouse) and its cloisters – plus the Museums, which are on three floors.

A great collection of Ancient Roman art is spread across five beautiful spaces and includes a large exhibit on pre-Latin peoples from the area and glass cases full of bronze- and iron-age pots. The collection includes some 20,000 inscriptions and is still being added to regularly. The second floor contains archaeological finds from ancient Lazio dating as far back to the 6th, 10th and even the 11th century BC.

Duck into Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, a huge church that was designed by Michelangelo in 1562, at the behest of Pope Pius IV, to house the remains of the ancient Roman bathhouse and to commemorate the Christian martyrs who were said to have died during the construction of the baths.

You enter through a giant brick niche from the Baths of Diocletian. There is a meridian sundial in the floor here that dates from 1702, and which was used to set Rome’s clocks for nearly 150 years. You would expect this church to be better known, given its enormous dimensions. Michelangelo designed the larger of the two cloisters in 1564, just before he died, and it’s one of the biggest in Italy, measuring and enormous 10,000 square metres, with a colonnade of 100 columns.

Places to wander around here are the peaceful 16th-century convent gardens called the Giardino dei Cinquecento (Garden of the Five Hundred), where I enjoyed looking at the sculptures of a Roman elephant and a Roman rhino. There are more than 1,000 artefacts, altars, sarcophagi and funerary sculptures on display in the gardens and surrounding cloister. Barely anyone was there when I visited. They don’t know what they’re missing.

Il Cimitero Acattolico Di Roma

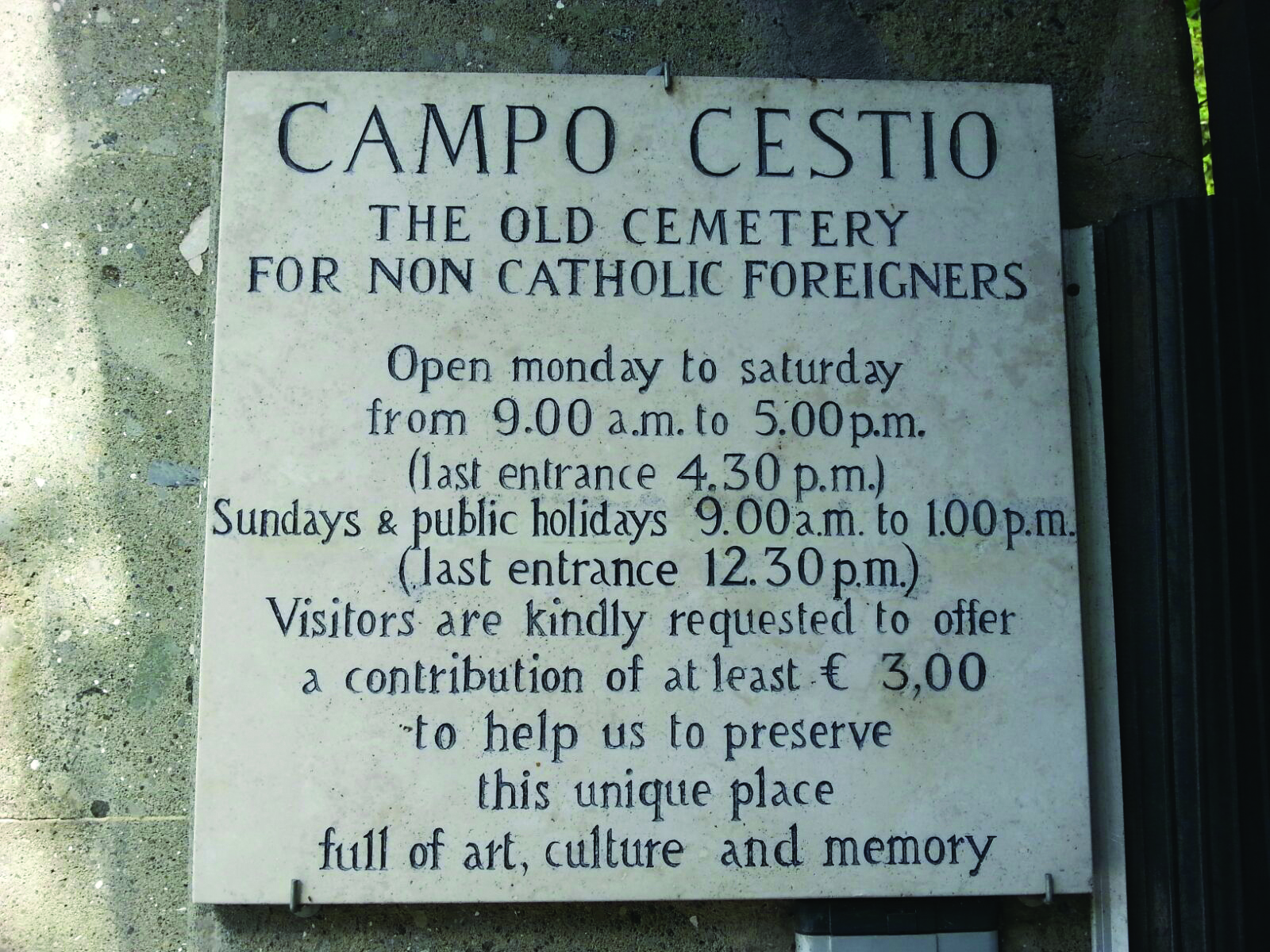

Campo Cestio, the Old Cemetery for Non-Catholic Foreigners

The Non-Catholic Cemetery began mushrooming out from the foot of the Cestius Pyramid nearly 300 years ago. Now it’s a densely packed graveyard brimming with sumptuous monuments and statues at every turn. It’s a little tucked away, right near the Pyramid (erected in 16 BC), in the lively Testaccio area and close to Rome’s Aurelian Wall.

I became intrigued by the mysterious and tragic stories behind the tombstones and was grateful for the shade provided by the cypress trees as I explored around the graves.

The origins of the cemetery go back to 18th century. The first person known to have been buried here was a young Oxford graduate called Langton. He was buried at the foot of the Cestius Pyramid in 1738 at 25. His remains were found a few metres away, but an official document pointing to the existence of the burial ground wasn’t found till 1748.

The burial ground was necessary because, according to the rules of the Catholic Church, non-Catholics couldn’t be buried in consecrated ground. Non-Catholics weren’t even allowed to bury their dead in the light of day. Mourners also needed to be protected from aggression, as there seems to have been little religious tolerance at that time. At the start of 19th century there was still no barrier between the burial place and its surroundings.

In 1824, Pope Leo XII gave permission for the oldest part of the cemetery to be surrounded by a moat – and this moat was the only protection the area had from vandals and drunks for half a century. Some of the moat still exists. And until 1870, crosses weren’t permitted on the graves, nor were inscriptions indicating ‘eternal bliss’. All inscriptions of the time had to be examined and passed by a papal commission.

“It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place,” wrote Shelley of the Campo Cestio shortly before he died.

A rich assortment of eminent painters, poets, writers, diplomats, sculptors, businessmen, composers, including the English poets Keats and Shelley, are buried here. Their graves are tended to by the Keats-Shelley Memorial Association.

Some gravestones are well maintained with abundant flowers and greenery, and others are a tangled overgrown mass of lichen and algae. More than 15 languages adorn the gravestones with nationalities including English, German, Scandinavian, Russians, Greeks, a handful of Chinese. Despite the different backgrounds, all those who are buried here shared a common love of the Eternal City. It’s been a popular pilgrimage site throughout its history, with Oscar Wilde visiting in 1877.

About 2,500 monuments are in need of upkeep and over 4,000 people are buried here, including some Italians. Around 80 per cent of the tombs aren’t being actively paid for, relying on support from Friends of the Cemetery, embassies in Rome and individual donors. Occasionally, stone conservationists from all around the world come and help out with the restoration.