You could travel the world’s museums to see the works of Antonio Canova, or you could go to Possagno, Joe Gartman writes…

Images by Patricia Gartman

There’s an elegantly mirrored and frescoed room in Venice’s Correr Museum, just off Piazza San Marco. I suppose you’d call the décor neoclassical: the mirrors are square, the frescoes are inspired by designs from Pompeii or maybe Nero’s Golden House, and there’s no rococo stucco work sprouting from ceiling or cornice. The room is dominated by an imposing sculpture in marble, showing an old man binding wax-and-feather wings to a young boy’s arms. The boy, of course, is Icarus; and the old man is his father Daedalus, the magically cunning inventor who created King Minos’s unsolvable labyrinth in Crete. We all know what happened when Icarus flew too close to the sun.

The marble figures were created by another wizard of invention, another artificer whose skill approached the magical, Antonio Canova. Made when he was 21 years old, in 1779, Daedalus and Icarus was one of his first commissions, and it began a creative lifetime during which Canova, like Icarus, rose to a perilous height: universal acclaim. Unlike Icarus, though, he managed to keep his wings intact, artistically speaking, and still is acknowledged as the greatest master of neoclassical sculpture – though, of course, neoclassicism has been eclipsed by a host of other ‘isms’ since his time, most of which melted away as quickly as Icarus’s wings.

Canova was by far the most famous and admired sculptor of his time. Like his great predecessor, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, he had an almost mystical ability to impart seemingly palpable life to marble. Bernini, of course, embodied the theatrical and flamboyant baroque style, which preceded the more restrained neoclassical manner theoretically inspired by ancient Greek and Roman artists. Some exuberant admirers compared Canova to the Greek Praxiteles or even Phidias, though nobody had actually ever seen an original work by either of them.

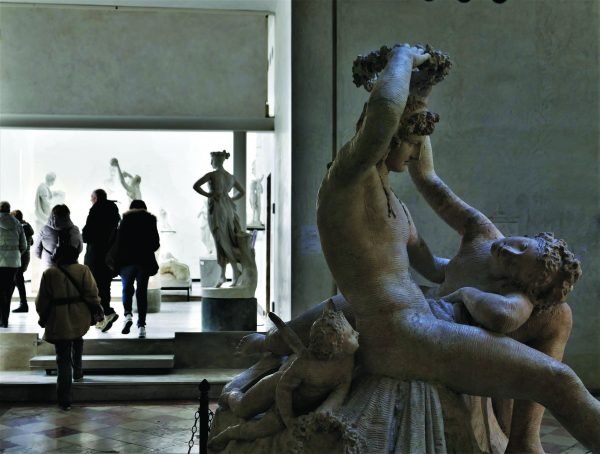

Restrained or not, Canova’s work still portrays passion, drama, and sensuality with great power, as you can easily see in sculptures like Hercules and Lichas, where the enraged hero tosses his terrified servant into the sea, or Adonis crowned by Aphrodite, as the goddess of love languorously curls her body around his, or… Well, actually, now that I think of it, you really can’t easily see many of his works. You’d have to travel the world visiting museum after museum… Unless…

Unless you visit Canova’s hometown, Possagno,in Veneto, about 40 kilometres northwest of Treviso, as I did a couple of years ago. There you’ll find the Tempio Canoviano, which looks like a half-size model of the Roman Pantheon, spectacularly perched high at the north end of Via Stradone del Tempio, at the foot of Monte Grappa. Canova had it built to serve as the town church.

At the south end of the Stradone is the Gypsotheca, built by Canova’s step-brother to house the priceless plaster casts from which Canova’s famous works in marble were created. Here, in an appropriately neoclassical 19th-century “basilica” (and a 20th-century addition by Carlo Scarpa), you can study Daedalus and Icarus and then, a few steps away, admire The Three Graces dancing just as gracefully as they do in London at the Victoria & Albert. The Penitent Magdalene kneels contritely both here and in St Petersburg, while Pauline Bonaparte reclines voluptuously as Venus Victrix with the same triumphant smile as in Rome at the Galleria Borghese. And you don’t have to travel to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna to see Theseus slaying the Centaur, either.In Possagno, dozens more masterpieces surround you, in an elegant setting made just for them.

One of Canova’s few failures was a monumental, eleven-foot nude marble figure of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker. Napoleon commissioned it in 1802, after the short-lived Treaty of Amiens. When the short, rather portly Emperor saw the finished piece, he exclaimed “Too athletic!”, and banned its display. The marble’s now at Apsley House in London, in what was the Duke of Wellington’s entry stairwell. (Vae Victis – “Woe to the Vanquished”, as the Roman Legionnaires used to say.) The plaster original is in the Gypsotheca.

Napoleon, during his absentee reign as King of Italy, had stolen many Italian artworks for the squares and museums of Paris. After Waterloo, Canova, representing the Vatican, was prominent in securing the return of most of them, including the bronze horses of San Marco; the breakthrough came when he met with Louis XVIII, who asked for a portrait in return. I don’t think Canova ever made one. Just as well.

The 17th-century house in which Canova was born is across a peaceful garden from the Gypsotheca. Beautifully maintained, it contains elegant furniture, paintings, and splendid exhibits showing how his works progressed from clay to plaster to marble. Even here, though, Canova’s personality is elusive. He was a liberal benefactor of Possagno, but most of his working life was in Rome – the plaster works in the Gypsotheca were transferred there from his Rome workshop after his death. He never married, though he was briefly engaged to a Roman beauty named Domenica Volpato, one of Angelica Kauffmann’s favourite models.

When he died in Venice of unknown causes, he was so revered that his relics were sought after as eagerly as those of a saint. Most of his body is interred in the Tempio Canoviano in Possagno but his right hand is in the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice; and his heart, also in Venice, rests in an urn behind the half-opened door of his monument in the Church of the Frari.

About the writer:

Joe Gartman writes about travel, history and culture, and divides his time between the southwest US and Europe. Learn more at www.joegartman.com