The final resting place of an English eccentric who made Venice his home, writes Joe Gartman

Images by Patricia Gartman

The pale red brick walls and tall cypresses of San Michele Island rise from the lagoon waters less than a quarter mile from Cannaregio’s Fondamente Nove. They form a perpetual memento mori, a reminder of human mortality, especially when a black boat, discreetly carrying a garlanded casket, makes its stately way toward the island, passing the floating sculpture of Virgil guiding Dante’s barque to the underworld.

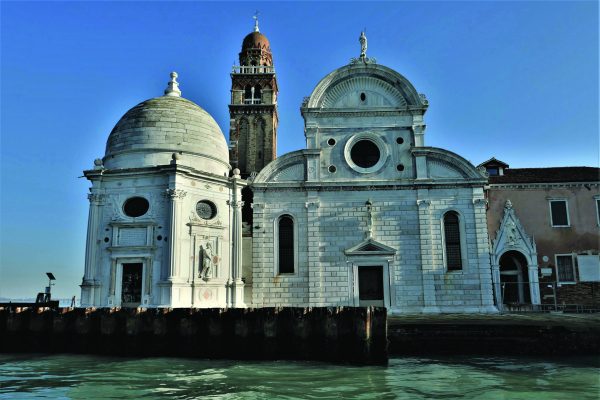

Once, Venice buried its dead in the walls and floors of its churches, even under the paving stones of church campi; and when it was needed, there was an ossuary on the remote island of Sant’Ariano where old bones displaced by new graves were deposited. In those days, Isola San Michele was home to a monastery and the elegant Renaissance church of San Michele in Isola, which dates from 1469; but the Republic fell to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797, and he declared burials in Venice unsanitary. So, after the island was enlarged by filling in the canal that had separated it from the neighbouring island of San Cristoforo, Isola San Michele became Venice’s new official graveyard.

Even now, most of Venice’s dead do not rest forever undisturbed. San Michele is a small island, and it has become increasingly crowded. Barring a few famous people, and wealthy families with long leases, most remains are exhumed after twelve years, perhaps to be re-interred in smaller, multi-tiered vaults, or disposed of in a mainland ossuary.

I used to idly ponder some of the famous residents, gazing at the island while waiting for a vaporetto; and finally, one day, I caught the boat toward Murano, but stepped ashore at San Michele instead. I had in mind a particular grave to visit, of someone whose fame is rather tenuous; but first I thought I’d seek out the resting places of the more celebrated figures.

Most of the island is filled with Catholic burials, of course, but in the small Orthodox section I found the grave of Sergei Diaghilev, the great impresario who founded the Ballets Russes in Paris. I remembered reading that he was so painfully afraid of drowning he wouldn’t board the ship that took his dancers across the Atlantic for a South American tour, but somehow he braved the Venetian canals during many visits to the city; and in 1929, after he died in the Grand Hotel des Bains on the Lido, a solemn procession of boats escorted his funeral gondola to the cemetery island. When I found his monument, it was hung about with worn-out ballet slippers and sprays of flowers – fitting tributes.

Igor Stravinsky, who wrote the music for both the Firebird and the revolutionary Rite of Spring ballets for Diaghilev, also had a solemn floating cort ge in 1971, when his casket, heaped with flowers, was rowed by four gondoliers to San Michele. He was buried near Diaghilev, in the Orthodox section of the cemetery; and in 1982, his wife Vera’s gravestone was laid beside his. I found a fresh rose on each, and on his, a collection of pebbles in the shape of a treble clef.

In the Protestant section, the grave of Joseph Brodsky, the Russian-born winner of the Nobel Prize for poetry, was marked with a modest granite stone. Ezra Pound was nearby, too; but I was eager to find the original object of my curiosity, whose reputation balances uneasily on the fulcrum between fame and obscurity.

He usually called himself Baron Corvo, though he was born Frederick William Rolfe, in 1860, in London. Raised as an Anglican, in his mid-twenties he converted to Catholicism, intending to enter the priesthood; but he was expelled from the Pontifical Scots Seminary in Rome for quarrelsome behaviour. Though he remained a Catholic, ever afterward he nursed a bitter grievance toward the Catholic clergy, and when he wasn’t being Baron Corvo, would sign his writings “Fr. Rolfe”, leaving the reader to decide whether “Fr.” was short for Father or Frederick. He tried his hand at painting, and then writing. He lived for the rest of his life on the meagre returns from his writing and the charity of friends. He was befriended in Rome by Duchess Caroline Sforza- Cesarini, and claimed it was she who gave him his baronetcy. He was charming, entertaining, difficult to evict, and thoroughly ungrateful. He often sent letters of complaint to his former hosts; few hands that fed him remained unbitten.

When he was in his forties, one of his generous friends offered to provide the necessary expense money for a sojourn in Venice together. His friend eventually found Rolfe’s “expenses” a bit prohibitive, and took himself back to England. Rolfe never left Venice, however, living on dwindling remittances from a few kind-hearted souls from his past. There were occasional writing commissions, including one describing his homoerotic adventures in Venice for the vicarious enjoyment of a wealthy English client. In time, though, he exhausted his resources. He died in October 1913, penniless and friendless.

Two of his books are still discussed and debated today: The Desire and Pursuit of the Whole, an odd fantasy about a failed writer and an androgynous teenager who becomes his servant, and Hadrian the Seventh, about a failed priesthood candidate who becomes Pope, “reforms” the church, begins to reshape the world to his taste, and is finally assassinated by an anti-Papist Ulsterman. Hadrian the Seventh was adapted by Peter Luke into a play in the 1960s, and had successful runs both in the West End and on Broadway. In an out-of-the-way part of the island, I think I found Baron Corvo’s tomb, embedded in a stone wall. I couldn’t see his name, though, because the wall was obscured by broken scaffolding. There were no flowers.

Enjoyed this article? Read more like it in our Italia! archive