Sicily has countless charms to tempt visitors, and here Francesca Unsworth visits the island’s second largest city to discover why it is a food-lover’s paradise

Catania and I didn’t get off to the greatest start. “Take a hike,” was the censored version of an insult shouted at me by a fishmonger yielding an intimidating cleaver in one hand, and a cernia (grouper), dripping with blood in the other. In his defence, I was documenting his skilful gutting and filleting of an enormous fish without his prior consent, mouth open in awe – apparent sacrilege in this historic fish market. While I can censor the language that escaped the mouths of gruff vendors, in the city’s pescheria scenes of gutting, de-heading and slithering live octopus were most certainly uncensored – an orgy of tentacles, shells and slimy fins. This is, after all, one of the most gloriously gritty markets in Italy, and the heart and soul of the city’s gastronomic culture.

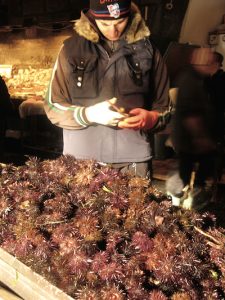

If you want to discover what is popularly eaten in the second largest town in Sicily, look no further than this hectic hotbed of trade in seafood and fish. An epic display of cockles, cratefuls of sea urchins, large chunks of swordfish and tuna, heaps of sardines and some unidentifiable curly shimmering silver flatfish that turn out to be spatola (scabbard fish), greet visitors under the ash-coloured arches near the port. The seas around Sicily are rich with varieties of fish but are renowned for their tuna, swordfish and sardines. The sheer freshness and delicate nature of the fish means that raw fish carpaccio is all the rage, particularly meatier swordfish and tuna. The sardine is celebrated in a number of popular dishes, so sampling the ubiquitous sarde alla beccafico is a must. Sea urchins are sold by the case-load and are often eaten like oysters (doused in lemon juice, then the pulp is scooped out) or used in spaghetti ai ricci.

If you want to discover what is popularly eaten in the second largest town in Sicily, look no further than this hectic hotbed of trade in seafood and fish. An epic display of cockles, cratefuls of sea urchins, large chunks of swordfish and tuna, heaps of sardines and some unidentifiable curly shimmering silver flatfish that turn out to be spatola (scabbard fish), greet visitors under the ash-coloured arches near the port. The seas around Sicily are rich with varieties of fish but are renowned for their tuna, swordfish and sardines. The sheer freshness and delicate nature of the fish means that raw fish carpaccio is all the rage, particularly meatier swordfish and tuna. The sardine is celebrated in a number of popular dishes, so sampling the ubiquitous sarde alla beccafico is a must. Sea urchins are sold by the case-load and are often eaten like oysters (doused in lemon juice, then the pulp is scooped out) or used in spaghetti ai ricci.

Activity in the fish markets gets underway in the early hours of the morning, but come 2pm all the makeshift stands are packed up and the vendors desert the streets and pile into local restaurants. By 4pm there is no evidence that any activity ever took place. A fleet of cleaners has already descended upon the streets in orange fluorescent jumpsuits, washing away the stench of fish guts and tidy piles of tossed-out miniature red mullet and trout heads, while seagulls scavenge above.

Activity in the fish markets gets underway in the early hours of the morning, but come 2pm all the makeshift stands are packed up and the vendors desert the streets and pile into local restaurants. By 4pm there is no evidence that any activity ever took place. A fleet of cleaners has already descended upon the streets in orange fluorescent jumpsuits, washing away the stench of fish guts and tidy piles of tossed-out miniature red mullet and trout heads, while seagulls scavenge above.

Historic ritual

When the fishermen are not working flat-out in the fish market they are resting hard in their homes. This historic market ritual, which has been played out for hundreds of years, contrasts dramatically with the burgeoning modern scene of designer bars and restaurants taking the town by storm. At first glance, Oxidiana, a slick Japanese restaurant with black walls and lacquer stools lined up along a sushi bar, seemed totally out of place, but after a while it became entirely apt for a place promoting fresh fish (often eaten raw like sashimi), with a cuisine so influenced by its various invaders. The city is on one hand traditional and rustic, while at the same time modern and avant-garde. This apparent dichotomy in culture and lifestyle is equally evident in the city’s gastronomy, where these extremes are also played out on the plate.

The island’s varied produce plays a large part in inspiring the dishes of the city – nuts, citrus, and salt from Trapani in the north west to mention a few. The ingredients themselves speak silently of Sicily’s history, as food writer Matthew Fort notes in his travelogue Sweet Honey, Bitter Lemons: “The history of Sicily is written on the plate.” The multiple facets of Catania’s culinary history can indeed be pinned down to a succession of invaders, (Phoenicians, Greeks, Arabs, Spaniards, Normans), who throughout the centuries have bestowed cultivation and preservation methods, as well as a plethora of exotic fruits and vegetables, upon the island. It was the Greeks who introduced the vines and olive trees which now form much of the landscape and produce the renowned oils and wines. The Normans get credit for salt-preservation techniques, which introduced baccalà and stoccafisso to the Sicilian table. Arab domination between 9th and 11th centuries brought arguably some of the most important culinary influences to the island in the form of nuts, apricots, saffron and sugar.

But none shaped the landscape and economy of the island quite like the introduction of agrumi, the citrus fruits. Some 90 per cent of Italy’s lemons are from Sicily, and around 40 per cent of its oranges. Citrus is to this part of Sicily what the San Marzano tomato is to Campania. Like the tomatoes, which are reputedly the best in the world thanks to the unique soil at the foot of Mount Vesuvius where they grow, northeastern Sicily has the spectacular citrus. The tarocco and moro, two prized blood varieties that thrive in the shadow of Mount Etna’s fertile soil, are enjoyed as they are or freshly-squeezed in local bars, more closely resembling a Bloody Mary than an orange juice. The pigmentation, flecks of red sometimes verging on black, is said to be most obvious in fruits from the foot of Etna.

But none shaped the landscape and economy of the island quite like the introduction of agrumi, the citrus fruits. Some 90 per cent of Italy’s lemons are from Sicily, and around 40 per cent of its oranges. Citrus is to this part of Sicily what the San Marzano tomato is to Campania. Like the tomatoes, which are reputedly the best in the world thanks to the unique soil at the foot of Mount Vesuvius where they grow, northeastern Sicily has the spectacular citrus. The tarocco and moro, two prized blood varieties that thrive in the shadow of Mount Etna’s fertile soil, are enjoyed as they are or freshly-squeezed in local bars, more closely resembling a Bloody Mary than an orange juice. The pigmentation, flecks of red sometimes verging on black, is said to be most obvious in fruits from the foot of Etna.

Cedro (known as ‘citron’) is also an agrume worthy of a mention as one of the most eye-opening discoveries on my visit to the citrus groves surrounding Catania. It is a fragrant fruit whose charm lies in its knobbly imperfections and unimaginably sweet rind, with not a hint of bitterness. The skin of these lumpy lemons is thick and fleshy, although there is little fruit within. I ate the rind of one while I was there and smuggled another home in my suitcase, where it subsequently went a long way, triumphing in a salad and served alongside some salmon. The rind of Sicily’s citrus fruits is equally important in its candied form, where it sneaks its way into the famous cannoli and cassata.

The noble aubergine (also thought to have been introduced by the Arabs) is the predominant vegetable on the table and is the protagonist in Catania’s most widely exported dish, pasta alla norma, lightly fried aubergines with pasta. Caponata, the sweet and sour aubergine stew, is often served as an antipasto, as is melanzane alla parmigiana. The prickly pear – known as fico d’India (Indian fig) in Italian – is one of the more unusual sights on market stalls in Catania. The fruit grows on a variety of cactus native to Central America and is cultivated around the foot of Mount Etna. In the past, the cacti were planted in hedgerows to protect the boundaries of houses from intruders, and though it might not serve the same purpose as it once did, the fruit is still enjoyed as a sweet, rubbery mostarda, shaped into fish moulds as in the past.

At the foot of Mount Etna, which lies snow-tipped and silent in the background despite being one of the most active volcanoes in the world, the city’s setting is as dramatic as the daily theatrics played out in the fascinating fish market. Catania’s cuisine is as exotic and intriguing as the city itself, even for the most seasoned Italian adventurer.

Click here for more Catania travel inspiration.