Decaying, flood-prone, overcrowded and expensive, Venice still manages to be the world’s most beautiful city. Perhaps even lovelier in gloom than sun, this is the capital of paradoxes, says Fleur Kinson…

Coming in to land, the aeroplane window frames views of a sodden, misty-grey landscape that fragments into the Adriatic Sea. It’s a world half land and half water, the boundaries between the two elements blurred. Sinking lower through the November sky, wheels clunking out from their sockets in readiness, the wide lagoon around the island of Venice grows distinct. You can trace the sinuous lines of its underwater channels and shallows – the wayward wriggles that put this extraordinary city here in the first place.

Venice came into being when people living round the shores of the lagoon needed to escape Attila the Hun. His murderous tribes swept down through Italy in the 5th and 6th centuries, forcing locals to seek refuge wherever they could. The labyrinthine water-channels of the lagoon proved a perfect protection, as it was impossible to navigate a boat safely through their shallows and sand-traps unless you knew them as intimately as the local people. Far out in the lagoon on the remote islets and mudflats which only they knew how to reach, living off fish and rainwater and seaweed, the early Venetians established their amphibious society. They drove wooden posts into the silt to create more land, and began fashioning streets out of water. From this strange and unpromising arrangement, they founded an island city that would become for a thousand years the world’s greatest trading state. And later one of its most loved tourist destinations.

Venice came into being when people living round the shores of the lagoon needed to escape Attila the Hun. His murderous tribes swept down through Italy in the 5th and 6th centuries, forcing locals to seek refuge wherever they could. The labyrinthine water-channels of the lagoon proved a perfect protection, as it was impossible to navigate a boat safely through their shallows and sand-traps unless you knew them as intimately as the local people. Far out in the lagoon on the remote islets and mudflats which only they knew how to reach, living off fish and rainwater and seaweed, the early Venetians established their amphibious society. They drove wooden posts into the silt to create more land, and began fashioning streets out of water. From this strange and unpromising arrangement, they founded an island city that would become for a thousand years the world’s greatest trading state. And later one of its most loved tourist destinations.

NIGHT VISITOR

From the airport, I take a water taxi to my hotel, sitting outside in the cold, sea-smelling air and clinging on for dear life as we bounce across the wakes of fast oncoming boats. A full moon hangs like a broken egg yolk, its orange circle smudged by the watery veils of evening sky. We drop our speed to inch quietly through the deserted back alleys of the city, the only sounds the drip of water and the imagined whispering of ghosts.

I’m struck by how profoundly beautiful Venice is at the tapering end of the year. The damp and dark make stark its graceful lines, its sympathetic melancholy. Crumbling plaster, tilting bell towers – decay is nowhere else in the world more attractive. The elegant rot inevitably sets you marveling that this impossible project, a city built on water, which was surely doomed to fail, miraculously and beautifully persists. Thus Venice appears as a valiant triumph over time, a glorious poke in the eye to mortality.

From the hotel I take another water taxi to Piazza San Marco. The boat docks expertly in the bucking waves, and I stroll into the grandest of grand squares – now fantastically spacious without its summer hordes. The basilica is ghostly grey and asleep, all its glinting gold put to bed for the night. A few pigeons huddle shivering, a welcome contrast to their bolshy swarming several months ago. On three sides of the piazza, pale arcaded buildings stand handsome and serene. It’s like catching a flamboyant stage-actor off-guard and asleep.

From the hotel I take another water taxi to Piazza San Marco. The boat docks expertly in the bucking waves, and I stroll into the grandest of grand squares – now fantastically spacious without its summer hordes. The basilica is ghostly grey and asleep, all its glinting gold put to bed for the night. A few pigeons huddle shivering, a welcome contrast to their bolshy swarming several months ago. On three sides of the piazza, pale arcaded buildings stand handsome and serene. It’s like catching a flamboyant stage-actor off-guard and asleep.

Come here in warmer months and this square is a heaving whirl of crowds, cameras and café-tables, backed by the magnificent gilded fizz of the basilica, watched over by the hot orange spike of the campanile. And in that midday heat, what do people drink? Coffee, of course. Piazza San Marco was long ago dubbed ‘the drawing room of Europe’ – the space where the whole continent meets to engage in genteel conversation. And talk always flows better over coffee.

In the early 1600s, coffee first entered Europe through Venice – then a great trading city with a semi-monopoly on luxuries from the exotic east. Europe’s very first cafés sprang up in Venice, and all the civilized delights of café culture slowly spread from here. The oldest surviving café in the city today is the Florian, tucked into a corner of Piazza San Marco. It first opened its doors in 1720, and quickly assumed the role of Venice’s informal heart of politics and art. The great, the good, the ordinary and the notorious have all supped coffee at the Florian in their time.

Casanova did some of his lady-hunting here, while Byron, Dickens and Proust were inspired by the café-characters they discreetly observed. I choose a room whose walls and ceiling are a blaze of oriental portraits, covered in gilt and glass that redoubles the tiny lights of the chandeliers. My fellow patrons are young Venetian couples, or a quiet tourist or two. I’m pleased to find a seat so easily. In the height of summer this place would be packed.

Venice currently receives more than 12 million visitors every year. It’s ironic that a city originally built to elude outsiders should now entice them in such abundance. The problem is that the place is just so gorgeous. For centuries, Venice spent much of its trading wealth on beautifying – building palaces and churches, carving statues, slapping on the gold. When the city’s wealth and power began to decline from the 1500s onwards, it steadily acquired a new reputation as a place of fun and frivolity. Aristocratic young men making the Grand Tour across Europe couldn’t miss making a stop in Venice. And so began a tradition which persists to the present day.

The modern tourists who clutter the city (and drive up its prices) are generally regarded as an irritant by other tourists. It’s often said that Venice is ‘ruined by tourists’. But in fact, the city has been saved by them. Not only have tourists sustained the Venetian economy, they have preserved the physical existence of the place. Without its immeasurable worth to visitors, Venice would long ago have slipped into the mud. Why go to all the trouble and expense of propping the place up if there weren’t a fortune to be made from it? So the invading camera-toting hordes should be thanked, really. The fact is that no individual visitor should ever be begrudged for wanting to behold the glories of Venice.

However, there are far more visitors here now than ever before. With a global population that has more than doubled in the last 40 years, many foresee that a restriction on visitor numbers to Venice may become a sad necessity. In the meantime, it’s worth considering an autumn or wintertime visit to relish not only the atmosphere but also some space and serenity.

However, there are far more visitors here now than ever before. With a global population that has more than doubled in the last 40 years, many foresee that a restriction on visitor numbers to Venice may become a sad necessity. In the meantime, it’s worth considering an autumn or wintertime visit to relish not only the atmosphere but also some space and serenity.

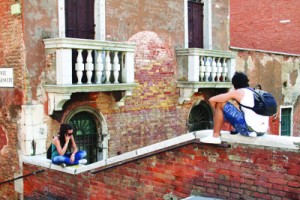

Happily, thanks to Venice’s unfailing gift for conundrum, even at the apex of the summer visiting season it’s still possible to stray onto a completely deserted back alley.

The liquid streets follow the old natural watercourses of the lagoon, and their dense, mazy intricacies mean that some alleys are rarely found by any but the most determined explorer. About 177 canals wriggle through Venice, creating about 28 miles of domestic waterside to stroll. This is a sublime city for aimless roaming on foot. Anonymous alleys are as much a part of the whole Venetian experience as the countless beautiful churches and the sumptuous art-treasures inside. But you are almost certain to get lost eventually!

Enjoy it as just another part of the mystery and romance of the city. The unsettling power of Venetian streets to lure you off on strange tangents – and occasionally lead you into disaster – is something wonderfully exploited in famous atmospheric films like Death in Venice and Don’t Look Now.

The next day, I’m out on the streets at an ungodly hour, knocking back cappuccino at a pavement café. Early morning Venice is ragged and beautiful, its decay even more apparent in the cold morning light. Rotting wooden stumps bristle from the water, rubbish bins overflow, and the canals are chugging with service-boats. I linger on a narrow landing stage and watch barges roaring past laden with supplies. Workmen stand on each one, sternly shepherding their cargo. They’re bringing all the day’s unglamorous goods into the city – crates of food, cases of beer, plastic items for shops. The boatmen appear as the unsung stage managers and prop assistants, enabling the grand theatre of each Venetian day.

Shimmering out in its lagoon, rising dream-like from its winter mists and its summer heat-hazes, sometimes it’s easy to believe that Venice is nothing but a grand illusion. How can it really be what it is? Or have been all it once was? The magic of Venice lies in its paradoxes, its many contradictions. It’s a city falling apart yet faultlessly beautiful. Its native population is dwindling, yet it remains crowded. It’s a city but it’s not really a city – more a living museum, arguably existing only to delight visitors. In Venice, the land isn’t land and the streets are the sea. It’s a topsy-turvy place that forever outwits you. You think you’ve grasped it, you think you know where you are, then you turn a corner and… yes, you’re lost again.

Venice always surprises you, continually juxtaposing things you think couldn’t go together. If there’s one view that most seems to sum up this city’s natural ease with contradiction, perhaps it’s the vista you get looking west in the evening. Beyond the fine bell towers and ornate frontages, above the arabesque windows and delicate roof tiles, the sunset sky glows orange and apocalyptic behind the industrial majesty of the Venetian suburb Marghera on the nearby mainland. Towering steel cranes rend the sky with harsh diagonals, storage tanks glower over the shoreline and rusty cargo ships drag their black burden through the waves. Improbably, these austere modern shapes harmonise perfectly with the frilly historic buildings in the foreground, and enhance the dramatic beauty of the whole scene. In Venice, it seems, anything is possible.

Venice always surprises you, continually juxtaposing things you think couldn’t go together. If there’s one view that most seems to sum up this city’s natural ease with contradiction, perhaps it’s the vista you get looking west in the evening. Beyond the fine bell towers and ornate frontages, above the arabesque windows and delicate roof tiles, the sunset sky glows orange and apocalyptic behind the industrial majesty of the Venetian suburb Marghera on the nearby mainland. Towering steel cranes rend the sky with harsh diagonals, storage tanks glower over the shoreline and rusty cargo ships drag their black burden through the waves. Improbably, these austere modern shapes harmonise perfectly with the frilly historic buildings in the foreground, and enhance the dramatic beauty of the whole scene. In Venice, it seems, anything is possible.